“Conformity is the last refuge of the unimaginative.” – Oscar Wilde

For most of the world, the hope for 2022 is that it is the least bad year of the last three. But for global financial markets, this feels like a far-too-lofty aspiration. Following years of surging returns formost financial assets over the past several years, despite the largest coordinated global economic disruption in generations, several signs point to imminent disruptions to the recent trends. Xponance’s diverse team of portfolio managers observe four core themes we believe will dictate the degree and nature of these disruptions:

- The fading effect of central banks and governments on markets. The steady unwinding of monetary accommodation in 2022 will likely lead to lower returns for equities, losses for treasury bonds, greater volatility and more importantly, a more challenging landscape over the next 10 years than in recent decades. 2022 is likely to be a year when a lot of the things we have gotten used to in the pandemic begin to reverse, particularly if they have to pull back faster and stronger than we have thus far experienced, and more than consensus and markets expect. Low nominal yields and negative real yields on bonds mean much of investors’ portfolios are now providing unacceptably low returns and more limited diversification. High equity valuations likewise reduce expected future returns, and so a market-cap-weighting approach increases this vulnerability by causing investors to hold more of the same assets that are now yielding less.

The FOMC has clearly lost its patience with the inflation surge. Similarly, the ECB is considering scaling back asset purchases as some policymakers place greater emphasis on the inflationary impact of Omicron than its possible growth-retarding effects. As 2021 came to an end, this put pressure on the short end of the curve, pushing up the 2-year yield and ultimately led to a curve flattening. Conversely, early 2022 market action saw a bear steepener as investors digested and ultimately confirmed an elevated inflation print not seen since 1982.The market now expects a more aggressive response than the Fed is indicating (with the first rate hike in March of 2022 followed by another three hikes this year). Relative to prior cycles, the long-end of the yield curve has flattened much faster and earlier, suggesting a lower terminal rate and perhaps a belief that we will return to the secular stagnation and weak inflation of prior decades. Additionally, with the 5/10 slope close to inverting long before the Fed even starts the rate hike cycle, investors appear to fear a policy mistake that may swiftly need be reversed. We believe that strong private sector balance sheets and the economic momentum built up due to the last two years of fiscal stimulus render this outcome unlikely. Historically, economic momentum like we have now is not as easy to mitigate as current discounting suggests. Finally, despite the recent yield curve histrionics, and impending reduction in quantitative easing, financial conditions are not and will not be significantly tighter presuming 3 or 4 incremental rate hikes.

Our fixed income team is expecting rates to be mostly range bound in 2022 with upward pressure on the front-end of the curve. This could cause borrowing problems for both companies and consumers, but with rates starting so low it is unlikely we will reach these levels next year. Given the transition to a higher rate regime as well as rates starting at such a low level, this will likely lead to treasury returns being near zero or slightly negative on the year with any positive returns coming from the excess return stemming from the spread sectors. The MBS market will likely continue to struggle with the Fed buying being reduced and the possibility of higher mortgage rates, but we think other securitized sectors still have some room to tighten more with CMBS and ABS continuing to look strong coming out of the pandemic. The existing and arguably impending market dynamics has elevated the portfolio discussion of structure vs credit risk. Given corporate leverage trends, lower default rates and decent refi cliffs, we think that the volatility in corporate spreads will be below past rate hike cycles; but that elevated volatility in 2022 in both rates and spreads will create meaningful opportunities for security selection alphas. Our U.S. Fixed Income platform’s market outlook may be accessed here.

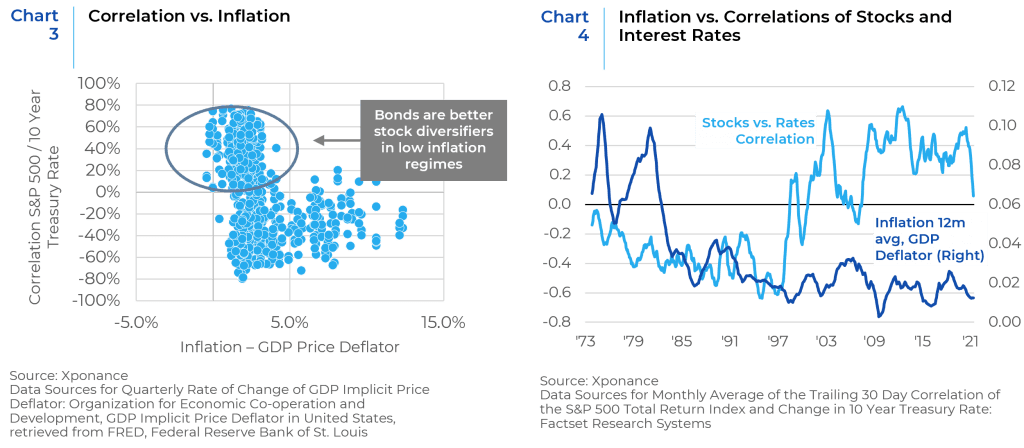

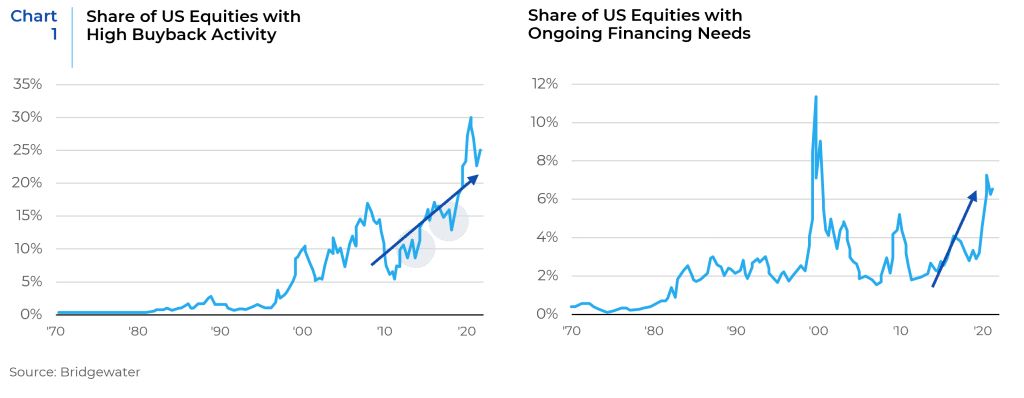

From a secular perspective, a decade of extremely easy liquidity has driven down discount rates, a mechanical support for equity market multiples that drove duration to secular highs. This poses a risk as rates begin to rise, especially for companies with very strong priced-in earnings growth and cash flows far in the future. U.S. companies in particular have also grown reliant on the ongoing flow of ample liquidity. Over the past decade, massive liquidity production has been enormously beneficial to US companies. Large companies changed their capital structure, issued debt, bought back their stock, and financed M&A, significantly boosting earnings-per-share growth. With less money flowing into the system, that funding will be harder to come by. As shown on the left chart below, the share of US companies that have boosted earnings-per-share via buybacks has increased significantly in recent years. You can also see here that recent periods of tightening liquidity (2013 and 2018) drove brief pullbacks from this trend of rising buybacks. In addition, liquidity has poured into innovative companies, many of which seek to “grow at all costs” and run significant cash flow deficits effectively financed by issuing equity. While these companies are still a relatively small share of the listed equity market (about 6%), their share has grown as they have increasingly gone public, and they represent a real vulnerability to the high-flying growth segment of the market.

For many companies, ongoing strength in economic activity will be a support that counters the impact of tightening liquidity. We expect that to be particularly true in markets like Japan and Europe, which are comprised of more cyclical industries and have some of the post-COVID economic bounce still ahead. By comparison, we see more risks for the US market, which has benefited more significantly from ample liquidity in recent years, faces greater pressure to tighten given growing inflation risks, and is already through most of the post-COVID rebound.

- Global diversification will finally be profitable. Over the last decade, global diversification has not paid off for U.S. investors and overweighting U.S. assets has been immensely profitable for non-US investors. However, relatively stretched valuations, rising debt and rates, inflationary pressures, limited monetary fuel and internal conflict all represent a combustible mix for US assets. While European asset valuations are less demanding, Europe is also challenged by too many IOUs, low productivity and domestic conflict. Emerging markets provide more compelling valuations on both the debt and equity side. Moreover, publicly traded EM equity markets are actually deeper than DM equities now, in terms of the number of liquid and neglected stocks for nimble active managers to choose from. This is especially true in China, now the world’s largest market in terms of number of investible, publicly traded stocks. Consequently, huge risk premiums have been built into emerging markets assets and low risk premiums have been built into US assets. So what spaces are less crowded, quite frankly emerging markets on both the debt and equity side.

COVID has also provided material relative support to US equities from all channels—favorable sector tilt, less virus economic impact, more support from falling rates (versus, say, Japan, where yields are pegged), and compressing risk premiums, given the safe-haven appeal for US equities. Over the last 18 months, markets and economies appear to have become increasingly resilient to virus-driven shocks, with responses growing smaller in successive waves. Barring a highly lethal mutation, the pandemic will become a much smaller market driver. We thus would expect the COVID impact to gradually fade in the coming year and this to be a relative support for the markets outside the US.

China could arguably represent the biggest risk and/or biggest opportunity. Specifically, how will growth, inflation, commodities, and geopolitical risks be affected by another great power rising to challenge the existing world order in trade. Additionally, how will trade, inflation, commodities be impacted by China’s attempt to rebalance its economy towards higher value and greener production and consumption? In our opinion, it would be a huge mistake for an allocator to not have exposure to China.; but because of the need to evaluate key exogenous and ahistorical risk factors, active strategies will outperform passive strategies in non-US and particularly emerging markets. Moreover, China is showing early signs of moving toward easing after a year when the structural goals (deleveraging, rebalancing, common prosperity, etc.) were prioritized. This again will be a bigger relative support for economies like Japan, Europe, and EMs that are more exposed to China. Our multi-manager team polled our emerging markets managers to obtain their views on China. The results can be found here.

Finally, if one looks back over the last 100 years, it’s almost always been the case that the winners of a given decade end up being laggards in the next one because of the degree of exuberance (and pessimism) that gets priced in following the winning (and losing) stretch. Given how stretched the relative positioning and pricing is today, we expect the US versus rest of world diff to finally start to revert after a decade-long off-the-charts performance. The main things we are watching closely are the evolution of COVID globally, China’s policy stance, and the retail flows in the US, which were the biggest support for US equities over the past year and a half.

- An Inflationary Regime Shift. Whether inflation will normalize to a 2 to 2.5 long trend once supply related distortions have been resolved or whether demand related factors such as wage inflation will lead to a longer term structural unmooring of inflation expectations. De-anchoring of inflation expectations are hard to predict and pernicious because they are undergirded by a psychological element or zeitgeist. A psychological inflationary feedback loop could be catalyzed by continued tightness in the labor market, and/or robust consumption (as consumers spend down the savings they have squirreled away during the pandemic), which would accommodate higher prices. If supply-side constraints continue, high commodity prices could also trigger a feedback loop.

The key risk for market participants is whether the recent spikes in inflation represent a regime shift. The inflationary 1970s led to hawkish central banks and bond investors (then referred to as vigilantes) that repeatedly overreacted to periods when inflationary pressures built up. Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s “cold bath” strategy to tame inflation (by hiking rates to as high as 20%) along with powerful disinflationary forces, such as globalization, caused a regime shift which thereafter was characterized by falling and/or stable inflation. By the 2000s, and especially the 2010s, inflation was no longer a concern for investors. During the ensuing era of flat-flation: (characterized by low and stable inflation and periodic deflation scares), bond vigilantes retired and were eventually replaced by what some have labeled as bond zealots. Central banks likewise came full-circle from targeting lower inflation and inflation expectations, to aggressively trying to generate higher inflation.

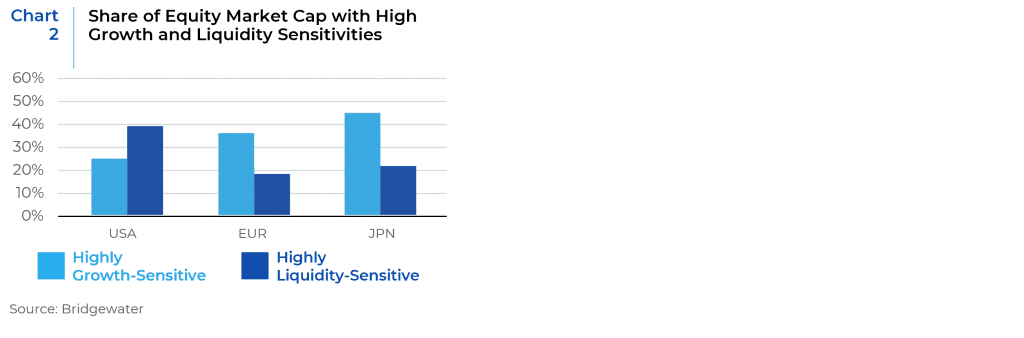

Additionally, the primary drivers of asset prices were growth, and a readjustment of the risk premium associated with major changes in market liquidity. Inflation became a far less important driver. Consequently, stock prices and bond yields became positively correlated while government bond prices/returns, and stock prices were negatively correlated. This dynamic enabled investors to easily diversify their equity holdings through bond allocations. Therefore, asset allocation models that simply evaluate relationships over the last three decades could be vulnerable to such a regime shift.

For asset owners, the key structural risk could arise from a regime change away from a low to a higher and more inflation regime which could upend the underlying assumptions that have been foundational to their asset allocation models. Our research on correlation in different inflation regimes suggests that the diversification benefit of owning stocks and bonds is disproportionately high in low inflation regimes. For example, during the high inflation periods of the 1970s and early 1980s, stocks and interest rates were negatively correlated, which means that stock returns and bond returns were positively correlated.

In the end, it is possible that the economic expansion could falter, and inflation once again retreat, with only a modest rate and yield cycle. However, betting on such an outcome does not seem prudent. But there are key trends that should render us open to the possibility that this time may indeed be different than the 2010s. The world economy and financial markets have undergone large changes in every decade during the post-WWII period, and thus it would not be surprising if another major shift in the landscape occurs this decade.

Few investors are positioned for a different inflation outcome, which should give cause for concern. As in the early 1980s, the bond market’s reaction (as measured by long-term rates expectations) to the Fed’s anti-inflation pivot is the same – disbelief and delay. Going into 2022, we are neutral in our exposure between value and growth because it is quite possible that as in the late 1990s, we have yet to see the last and most powerful leg of the growth bull market, particularly if inflation disappoints next year. Looking at fundamental data, 2022 EPS growth forecasts slightly favor value stocks or growth stocks (at 10.0% versus 9.5%). In fact, small-cap value stocks have the highest 2022 growth projections (16%) of any of the six style market segments. Thus, value may now be a better growth option given the price to access it. Beyond these fundamental dynamics, there are macro reasons to favor value. In an environment characterized by rising rates, cyclical industries and short duration value-oriented names tend to perform well. Over the past 30 years, growth stocks’ monthly excess returns to the broader market have a negative correlation to changes in interest rates (-17%), whereas value excess returns are positively correlated (+18%).

Our Systematic Equity platform’s market outlook can be accessed here.

- Climate change will likely to be one of the defining issues of the 21st century, affecting economies and markets in different ways. The global imperative to get to net zero will require incorporation of climate risk exposures into financial reporting and all asset risk underwriting. Over time, achieving the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions likely requires a large reduction in commodities such as coal, oil, and natural gas and a transition to sources of energy that don’t emit greenhouse gases. There are many ways for such a transition to play out in markets, depending on the approach and choices policy makers make. Thus far, policy makers are using two primary methods to curb emissions: (1) pricing carbon, which seeks to raise the cost of energy sources that emit greenhouse gases (as Europe is leading the world in doing); and (2) supply squeezes for the “dirtiest” energy sources—which we’re seeing in many places (e.g., China has limited some carbon-emitting activity directly, and in much of the world, investors are unwilling to finance new coal plants). Both of these approaches are inherently inflationary because they raise the price or restrict less-green energy sources as a tool to incentivize replacement green energy capacity, but without directly adding to capacity. The tools are increasingly creating large impacts on commodity markets, and these in turn will have knock-on effects on the global economy.

This week, our CEO & CIO, published an Inaugural newsletter blog, “Frankly Speaking”. This month’s blog examines the parallels between both our collective vulnerabilities and our responses to the global pandemic regarding another planet-scale disaster, climate change. This blog can be accessed here.

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospects for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct, but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.