“Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” – Winston Churchill

Like many global investment managers, we have been asked by asset owners, their consultants, and the media about our exposure to Russia as well as our perspective on the investment impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We have summarized our opinion as well as that of the boutique managers on our multi-manager platform elsewhere (What Our Boutique Managers are Saying about Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine). Our updated views on the Ukraine invasion and the impact on China can be found in the inset below. In this research note, we would like to focus on structural changes in the geopolitical landscape that we believe have enabled Russia’s revanchism and will continue to elevate risk premia well beyond the resolution of the current crisis. For the first time since World War II, the United States is facing powerful, aggressive adversaries in both Europe and Asia seeking to recover past glory by reclaiming territories and spheres of influence. Both countries’ expansionism is symptomatic of America’s fraying clout as the singular global hegemon towards a more multi-polar world dominated by regional powers. This thesis, which was posited in my 2017 research note A World Without America, presages a more volatile, less efficient, and more inflationary global economy; coupled with higher investment risk premia and changing correlations for traditional “safety assets” in asset allocation models.

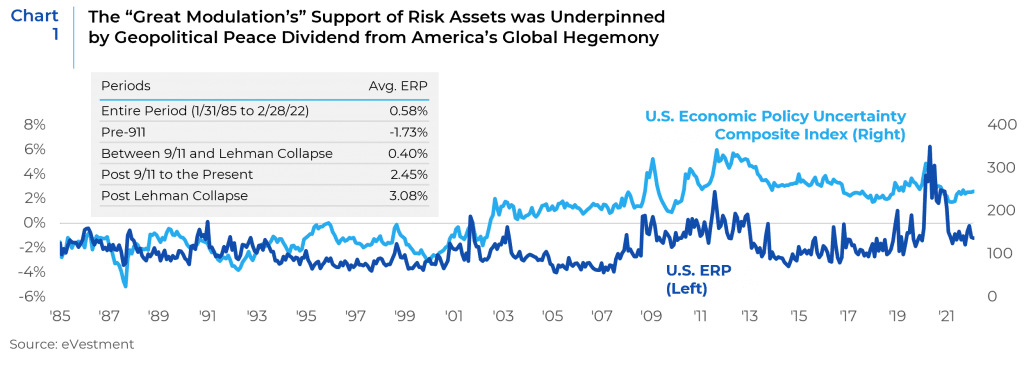

Why should investors care about fundamental changes in the geopolitical order? We would posit that these changes in the geopolitical world order are foundational to the long-term risk premia attached to investment assets. For example, the 30 plus year bond bull market is as much a result of the deflationary impact of trade globalization (primarily catalyzed by China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization), as was Fed policy. Similarly, the low equity risk premia (ERP) between the end of the Cold War in 1991 and 9/11/2001 was also underpinned by relative geopolitical stability. Since 9/11/2001, arguably an early warning of a destabilizing world, the ERP began to march steadily higher. (Chart 1).

Thus far, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has been crudely executed and appears to have been a significant geopolitical miscalculation which is likely to weaken Russia and could lead to regime change. Putin has 4 choices: lose early, lose late, lose big, or lose small. His Plan A – that because of Ukraine’s historical connection to Russia, its people would welcome annexation once the few “Nazis” running the country were quickly removed – is a fantasy. Plan B, if it exists, has yet to be revealed. Ukraine is a country of 44 million people. The only way he can stay in Ukraine is by permanently maintaining troops there and facing nonstop insurrection from the Ukrainian people. Ukraine’s largest trading partner was the EU, not Russia. Therefore, if trade with the EU is abrogated, Russia (population 142 million vs 447 million in the EU) is unlikely to be a comparable substitute, particularly with global sanctions in place. The freezing of the Russian central bank’s sizable reserves, is the equivalent of an economic nuclear strike against “Fortress Russia”, which increases the possibility of popular foment by a citizenry whose savings will have been demolished. The obvious though hopefully low probability – concern is an actual nuclear strike of some kind in response. It is worth noting that every failed war waged by Russia ended with regime change. Czar Nicholas I lost the Crimean War (1854-1855) to an alliance of European powers and was replaced by Alexander II; Czar Nicholas II’s 1905 loss to Japan fomented domestic discontent which ended in his abdication to the Bolsheviks in 1917, and Leonid Brezhnev was replaced by Mikhail Gorbachev at the end of the Cold War, from which the West emerged victorious.

For China, the Ukrainian invasion is a potential win-win proposition. If Russia prevails, it will be a stronger partner who is also opposed to Western international organizations and alliances. If Russia does not prevail, China will be an even more important independent geopolitical arbiter. Additionally, the further weaponization of bank reserves and the SWIFT interbank system feeds into Beijing’s argument for an alternative system for cross border financial flows and reducing the prominence of Euro-American reserve assets. With respect to Taiwan, Beijing doesn’t face the same constraints that Russia faces for Ukraine. The Chinese army is substantially larger and more sophisticated, possesses more extensive surveillance tools to stymie dissent, faces more favorable demographics and unlike Ukraine, Taiwan is not formally recognized by the west as an independent country. However, China’s strategic patience, coupled with Xi’s domestic challenges as China tries to grow its way out of a middle-income trap, will likely be a deterrent for now.

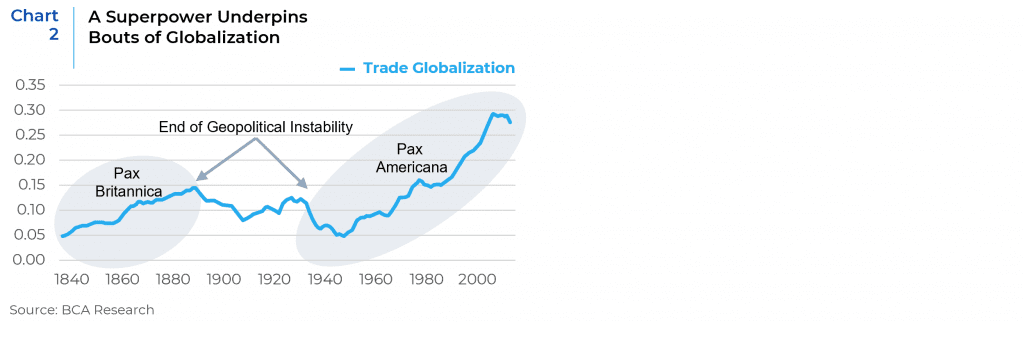

- We are rapidly becoming a multi-polar world driven by the interests and constraints of regional power blocks rather than a single global power. America’s 100 plus year reign as the global hegemon was preceded by a 70-year reign of the British empire as the singular global power, (which ended in the early part of the 20th century). By providing expensive global public goods – such as funding international institutions, dictating global commercial arrangements, arbitrating regional disputes, securing sea lanes as well as providing the world’s reserve currency – not only did both superpowers amass heretofore unparalleled wealth and power, but they also allowed other countries to focus inwards, industrialize and eventually catch up with their hegemonic patron. Additionally, in both cases, the expenses associated with their predominant position along with inevitable campaigns of militaristic overreaches, strained their economic resources relative to countries who were free to focus on internal development who could then export competitiveness under the safe harbor of relative stability provided by the dominant superpower.

A waning global hegemon is inherently less stable because the diffusion of power caused by the decline of a more inwardly focused global leader leaves a power vacuum for other countries to assert their own regional agendas. Thus, both World Wars were symptomatic of Britain’s decline as the only superpower which mattered. Today, Russia’s increasing aggression to reassert its regional dominance over its former vassal states; China’s assertions in the South China Sea and Japan’s consequent efforts to re-militarize; as well as Saudi Arabia and Iran’s competition for regional authority, are all symptomatic of controlled fissures that have re-erupted as a result of their increasing geopolitical significance, as well as America’s relative retreat from being the global policeman. Geopolitical uncertainty increases because the world transitions from one of relative cooperation under the rules and institutions imposed by the superpower (such as the WTO, NATO, the IMF and the World Bank) to a less stable zero-sum order.

- Retreating trade globalization in favor of regional trading blocks, countermanded by greater digital connectivity. (See Chart 2). The supply chain disruptions precipitated by COVID as well as the more mercantilist trade policy of the prior administration have accelerated this trend. So, for example, nation states’ desire to build their own semiconductor fabrication plants to protect their access to a key input for most 21st century products, will be undoubtedly less efficient than unfettered global supply chains that are primarily driven by costs, capabilities and logistics.

In a world carved into regional spheres of influence, each node, (say Russia, with respect to energy, palladium and grain, or China with respect to their domestic markets, manufacturing capacity and key minerals such as cobalt in the Congo), may impose more stringent mercantilist barriers to serve their respective geopolitical interests. This would theoretically benefit those countries that are least dependent on trade for their economic survival, such as America, for whom exports represent only 12% of GDP. America is also a relatively “low beta” market which typically outperforms in times of geopolitical uncertainty. Its geographical isolation, which has traditionally spared America from global conflicts is not immune however from new modes of warfare, such as cyberattacks.

Despite policy-makers’ attempts to erect firewalls, digital interconnectivity will continue to flatten the world. For example, the digital revolution enabled millions of global citizens to “cancel” Russia through an equivalent “Ukraine Lives Matter” movement which has pressured both state and non-nation state actors, such as businesses and pension funds, to pull out of Russia. According to Equinix’s Global Interconnection study, direct, private connections that bypass the public internet are expected to grow at a CAGR of 46% over the next 5 years, which is almost double the prior year’s predictions.

- Structurally higher inflation. Globalization is inherently deflationary as it allows corporations to source labor and resources from the most inexpensive sources. Therefore, a retreat from globalization will stem the deflationary impulse which has suppressed global bond yields and underpinned the 30 plus year bond bull market.

The commodity supply shock caused by the war in Ukraine exacerbates inflation levels that had already been at 40-year highs. These circumstances echo 1973, when an oil supply shock driven by geopolitical events in the Middle East exacerbated already building inflation pressures. The 1973 oil shock also slowed growth, making it more painful for policy makers to tighten in response to accelerating inflation. There are many differences between today’s economy and that of the 1970s—commodities make up a smaller share of GDP, and a less unionized workforce and a more digital economy make inflation less likely to compound. There are also large differences between countries’ vulnerability to a commodity supply shock today, as the U.S. is now a net oil exporter while Europe is likely to experience a larger growth hit.

Like today, both the Fed and the markets consistently looked through the rise in inflation, assuming it would not be sustained, and that significant tightening would not prove necessary in response. Then as now, inflation was consistently higher than what was priced in by the market. Policy makers also fell behind on tightening because of the exogenous, one-off nature of the shock and the risk to growth. It took over a decade of rising inflation before the Fed raised real interest rates in a sustained way—i.e., tightened more than inflation was already rising, such that the real cost of capital rose. Today, the picture is even more extreme, with monetary policy getting significantly easier as inflation rises, while nominal rates have largely not moved. As a result, real rates are more negative than they were in the ’70s and falling.

- Investors should re-acquaint themselves with higher risk premia and a greater likelihood and frequency of left-tail risk events. The combination of more interconnected global markets and the increasing market relevance of algorithmic funds and high frequency trading strategies could amplify such events. This is because many of these strategies embed similar algorithms that tend to close their positions when market volatility increases. If their positions are highly levered, they could cause a systemic market shock. For asset owners, now may be the time to re-evaluate certain hedge fund strategies, such as managed futures that are more suited for asymmetric risks.

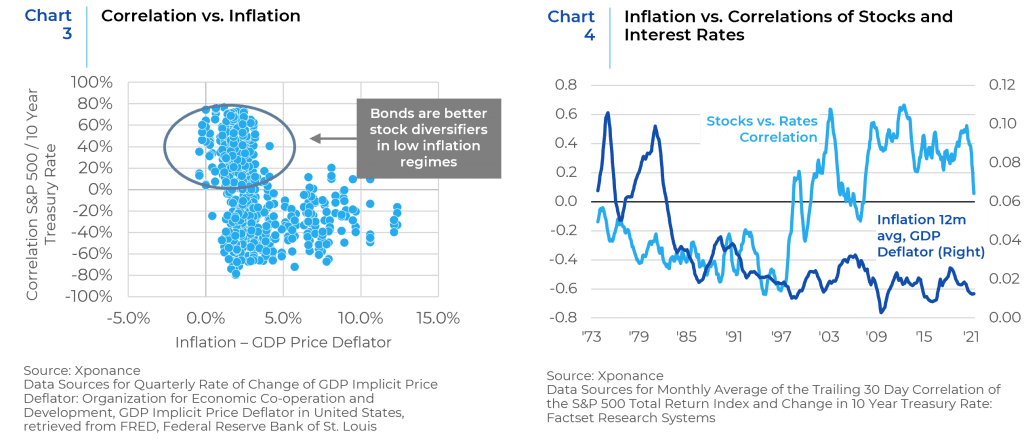

- Changing relationships in variables underlying asset allocation models. For asset owners, a more inflationary environment could upend the underlying assumptions that have been foundational to their asset allocation models. Our research on correlations in different inflation periods suggests that the diversification benefit of owning stocks and bonds is disproportionately high in low inflation regimes. For example, during the high inflation periods of the 1970s and early 1980s, stocks and interest rates were negatively correlated, which means that stock returns and bond returns were positively correlated.

Investors may need to reevaluate their allocations to traditional risk-free and equity risk diversifying assets in favor of so-called “anti-fragile” assets, that have traditionally thrived in volatile geopolitical and inflationary times. Commodities (both hard and agricultural) have traditionally thrived in such environments, as have real assets, cash and gold. Wheat for example, is a direct play on the naval blockade that Russia has now imposed on Ukraine. Cryptocurrencies’ purported inflation hedge properties are untested, and they plummeted early this year when the Fed formally announced that it would be raising rates to address spiking inflation; but it is worth noting that cryptocurrencies have soared since the latest round of sanctions were imposed on Russia, burnishing their touted credentials as a potential gold alternative.

- For long-only portfolios, defense companies (cyber and physical) should outperform. Global trade restrictions are likely to challenge the profit margins of multinationals and favor small cap stocks with predominantly domestic revenues. Moreover, the benefits of low-cost index strategies in emerging markets are likely to be outweighed by active managers’ who can skillfully incorporate exogenous risks.

In conclusion, Russia’s revanchism is symptomatic of a multi-polar world which will require asset owners to re-acquaint themselves with higher risk premia, higher structural inflation and a greater likelihood and frequency of left-tail risks. This fundamental shift will require asset owners to reevaluate assumed asset correlations, risk-parity strategies and downside protections embedded in their asset allocation models. All ground shifts create new winners and losers. We have highlighted the most likely winners: commodities, real assets, cash, managed futures, active managers, defense stocks, U.S. small cap and possibly, cryptocurrencies. Some of these assets (notably fossil fuel and defense companies) will need to be weighed relative to asset owners’ ESG goals; through strategies ranging from avoidance, to choosing companies within these sectors with the highest ESG scores, to investing in technologies that provide greener alternatives (whose substitutionary benefits would presumably be enhanced by higher hydrocarbon prices).

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospects for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct, but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.