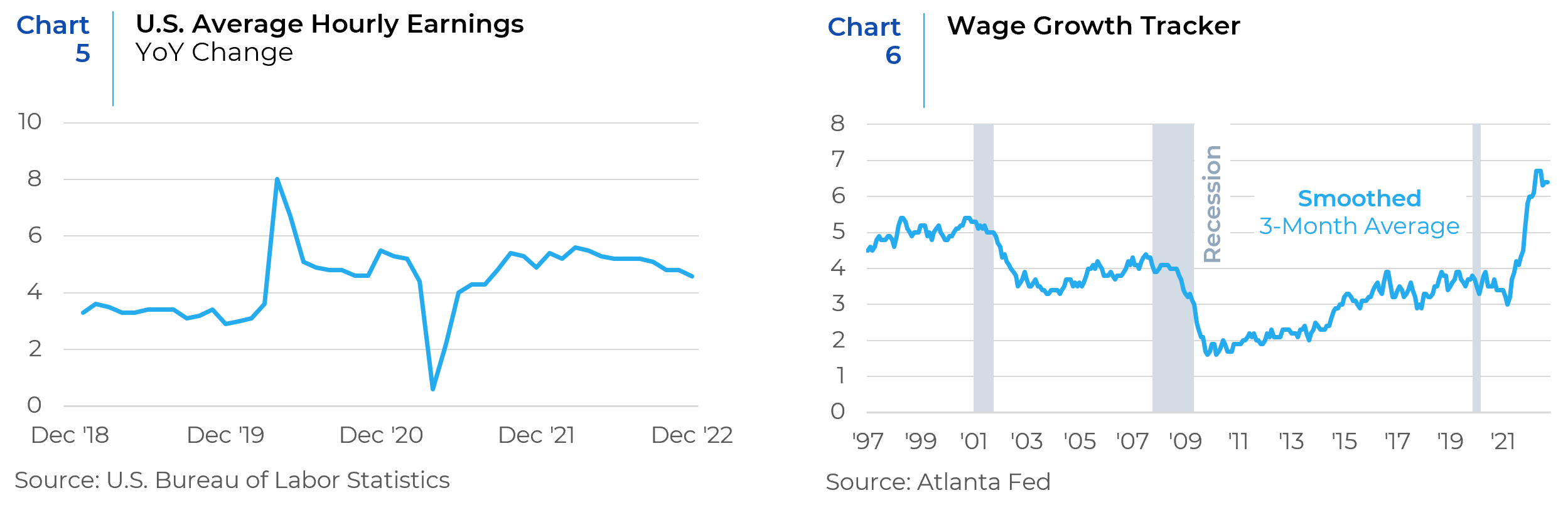

As we move forward into 2023, what happens in financial markets will be determined by the interplay of two primary factors – inflation and economic growth. Investor worries are transitioning from high inflation to low growth. Investors are concerned that the Fed’s focus on lagging indicators is risking a policy mistake. Such concerns were best evidenced by deep curve inversions and a sharp decline in excess liquidity as we closed out 2022. Corporate earnings growth remains another big overhang on sentiment as 2023 outlooks continue to highlight downside risk.

After being behind the curve in 2021, central banks have now become dedicated inflation fighters. To regain their credibility, they now risk tightening monetary policy excessively into 2023, inadvertently creating downside risks to the consensus soft-landing scenario. The culprit here is the lagged response of inflation, housing, and the real economy to central bank policy tightening. However, once the ball gets rolling, it rolls fast. The question that is now being asked the most is will the Fed “overshoot” and send the economy on a downward spiral or will it be able to navigate the economy through a mild recession and back into moderate growth? Ultimately, the performance of equity markets will be determined by the emergence of three peaks – peak inflation, peak rates, and peak dollar. While these peaks are in sight, they have yet to be reached. The last leg of a steep climb towards the peak can prove treacherous and markets tend to overshoot at this stage. That implies more short-term pain following an already dismal year of performance. 2023 will likely be a recession year where the three peaks will be reached. Once that happens, we expect a considerably brighter return outlook for major asset classes. Thus, the coming year may become a tale of two halves with a turning point in the market to materialize in the second half of the year. Until then, we expect volatile and muted equity returns.

The Inflation Puzzle

In 2022 inflation was primarily driven by the gap between policy fueled aggregate demand for goods and services and constrained supply, due to continued supply chain blockages. As we transition to 2023, the Fed continues to resort to demand destruction to tame inflation, whilst supply is improving meaningfully across the world. This could result in a significant decline in inflation unless another commodity price spike or supply shock reoccurs.

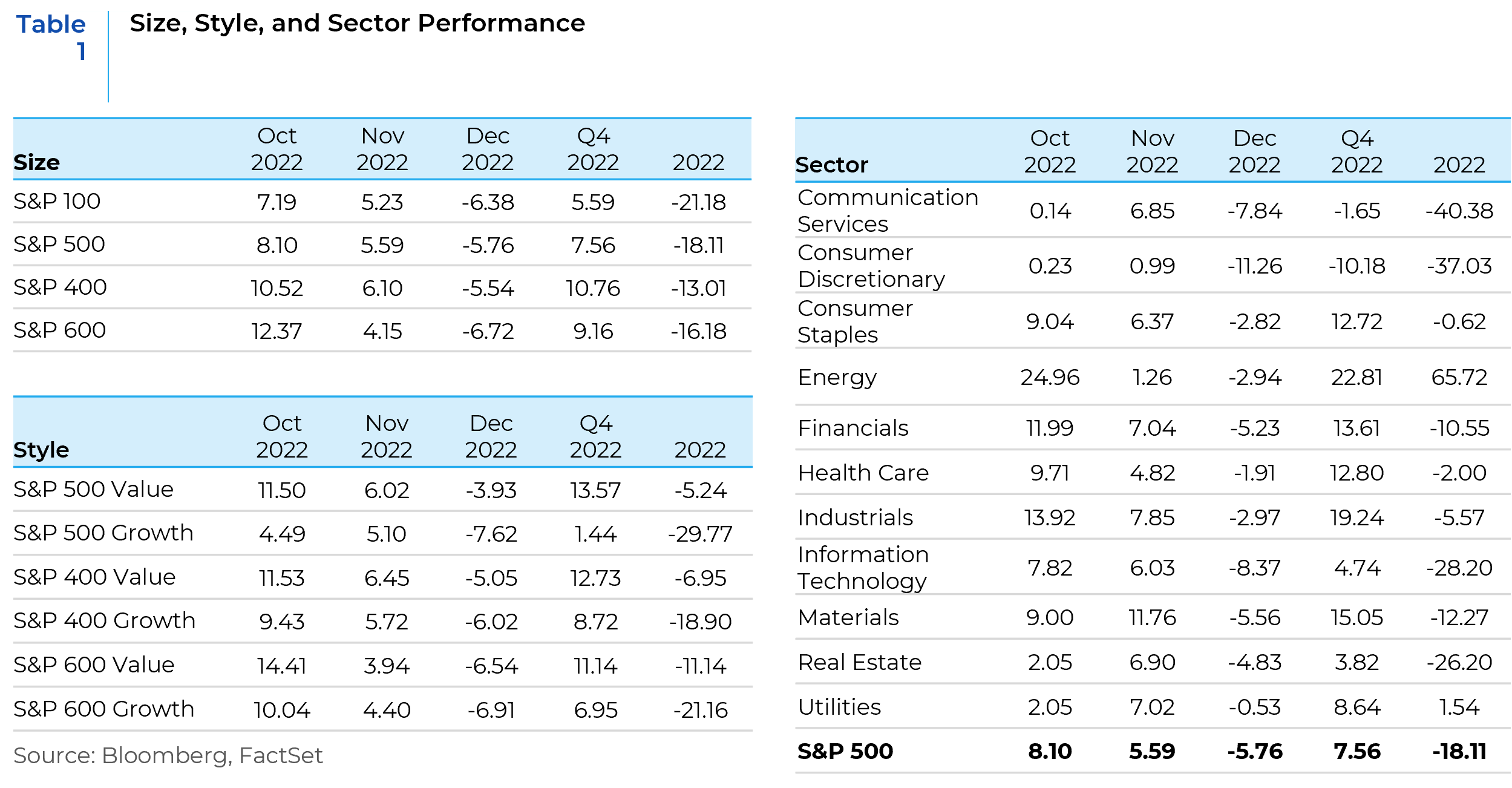

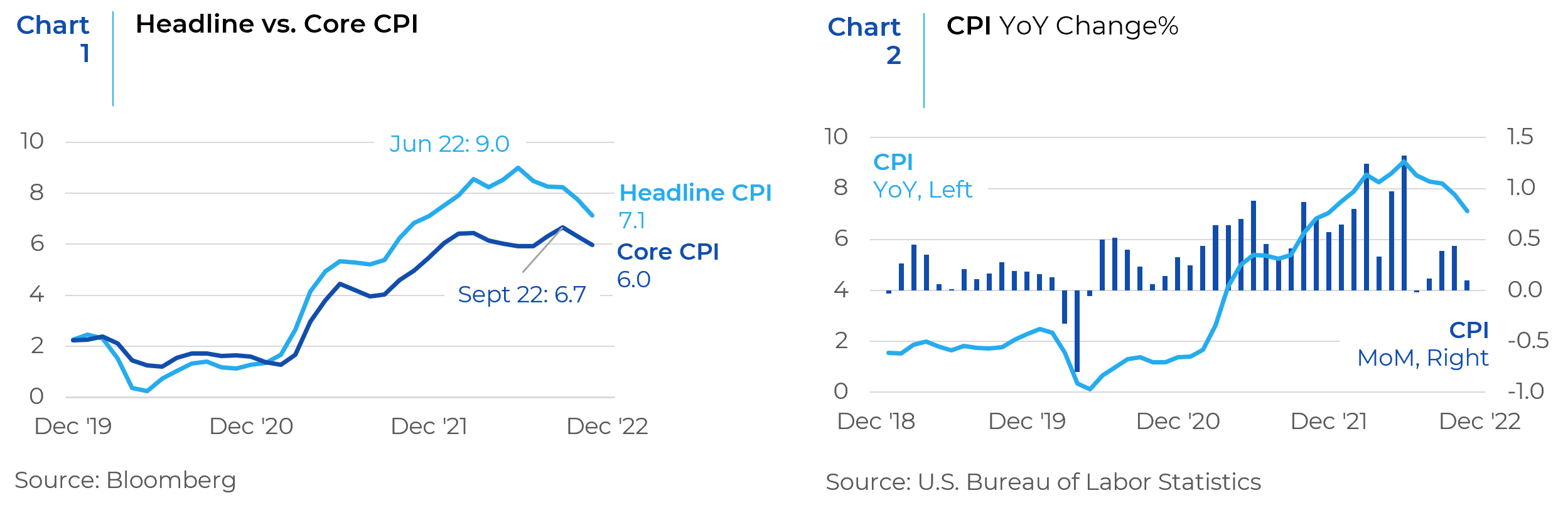

Both headline and core CPI readings appear to have peaked in an encouraging sign of stabilizing inflation (Chart 1). The YoY rate has eased for four months in a row now and the monthly gain in the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) has also averaged down (Chart 2). All of this data suggests that headline inflation may be losing some momentum.

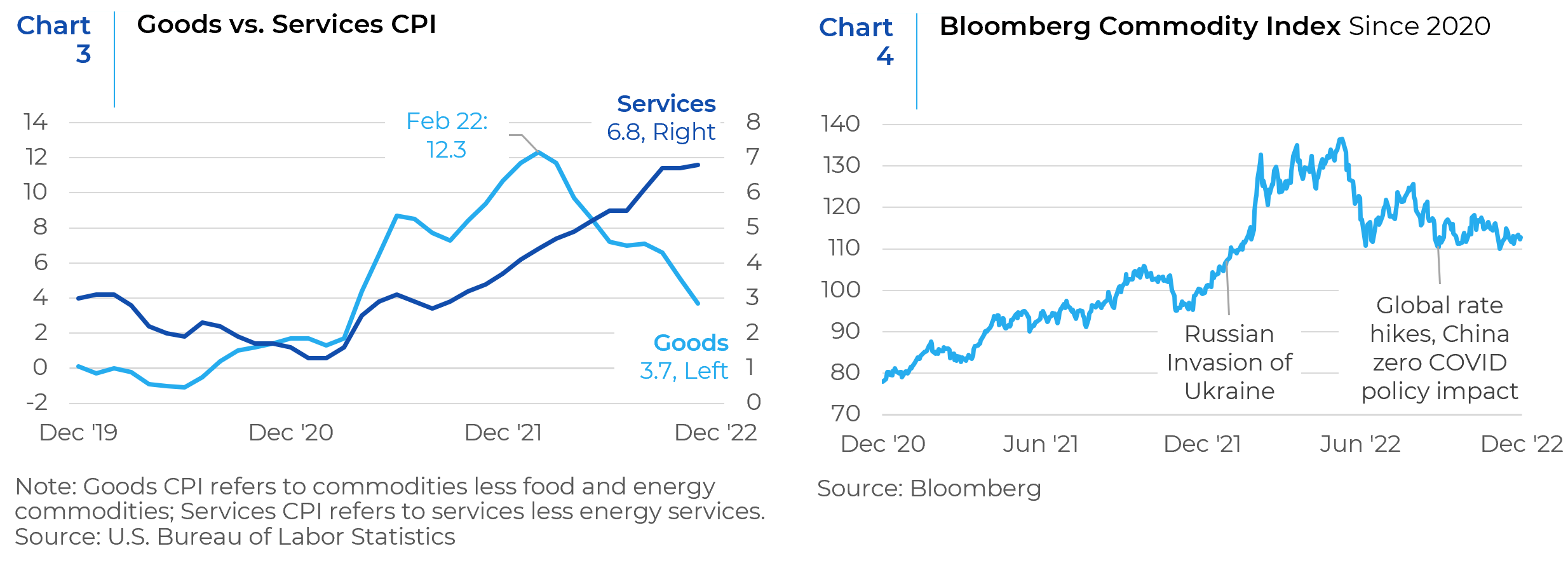

However, inflation in services and wages have proven to be stickier (Chart 3). The source, persistence, and direction of inflation will be the most important factors in determining Fed action in 2023. In addition, commodity prices also pose a risk to inflation. As shown in Chart 4, the Bloomberg Commodity Index has dampened as 2022 progressed but still remains higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The inflation puzzle therefore still seems far from being solved. Average hourly earnings remain high in defiance of the Fed’s efforts to tamp down the economy and wage growth is proving too stubborn for a Fed keen on holding down inflation expectations (Chart 5).

Moreover, the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s wage growth tracker corroborates the trend, showing headline 3-month wage growth of 6.4% in November, as shown in Chart 6.

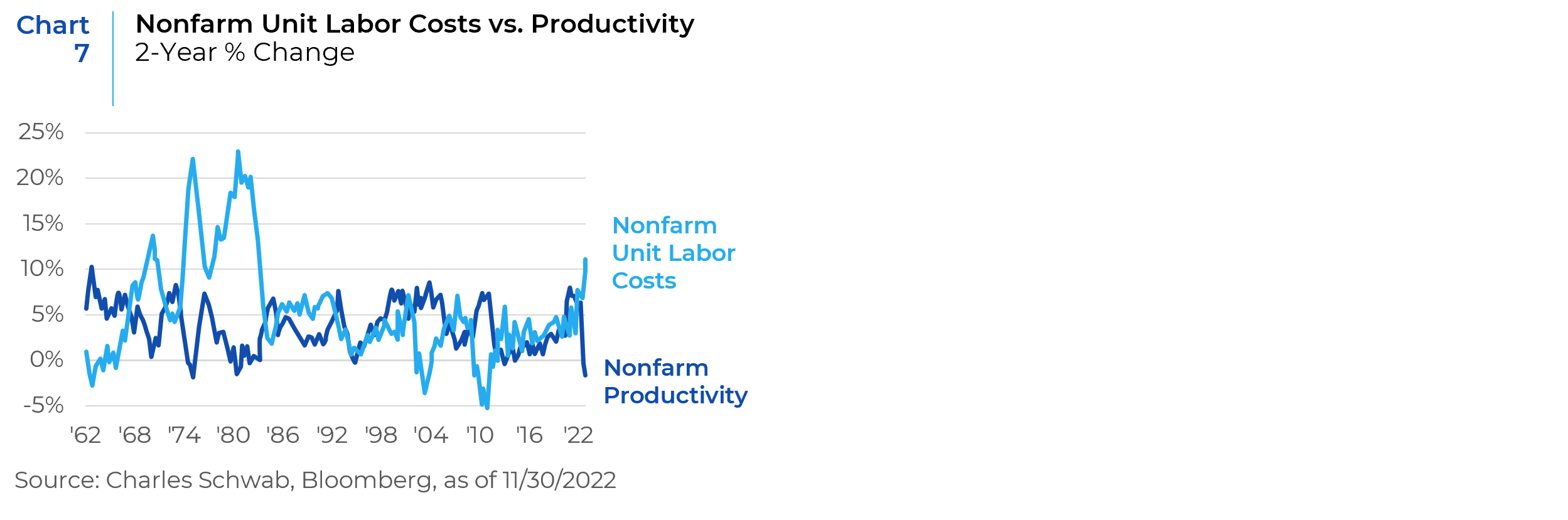

The Fed wants to create more labor market slack without causing lasting damage in the form of a high unemployment rate. That is a tough goal given the lagging nature of the unemployment rate. Therefore, the Fed is likely still far from declaring victory on the inflation front. Stronger wage growth goes hand-in-hand with higher unit labor costs, which are in turn highly correlated with inflation. As seen in Chart 7, the two-year percentage change in unit labor costs rose to 11.2% in the third quarter, the fastest since the early 1980s. Such gains unfortunately have been paired with a 1.4% drop in productivity, the worst since 1975.

Unit labor costs and productivity are both lagging measures, but higher-frequency data continue to underscore higher employment costs and weak productivity growth. As is the case with inflation at large, despite early signs of abatement, the pace of change in labor markets is too slow for the Fed to take its foot off the brake. With the Fed committed to taming inflation, unemployment will eventually have to rise. Payroll gains in goods-producing industries have begun to soften, likely due to the combination hangover from extensive purchases during the pandemic and rising borrowing costs acutely hitting big-ticket items. Services, however, have yet to show meaningful slowing. Until unemployment picks up modestly along with inflation forecasts coming down meaningfully, the Fed will not be ready to ease rates.

The Growth Conundrum

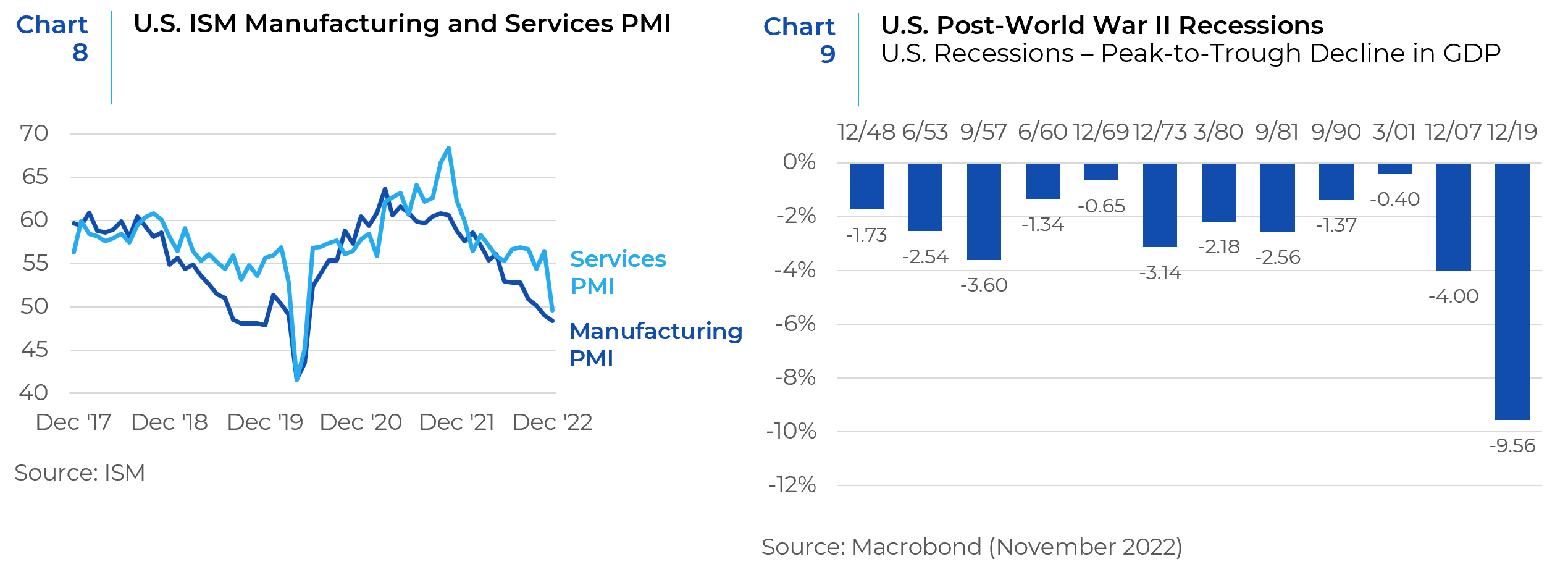

Most indicators of growth are pointing to a material risk of a slowdown, if not an outright recession. Both the ISM manufacturing and Services PMIs are inching towards contractionary territory (Chart 8). Growth engines driving the US consumer have also started sputtering and a deflating housing and stock market will dent the wealth effect. As 2023 progresses, we expect further weakness in housing and the most interest-rate-sensitive components of consumer spending, and for this to then spread to consumption more broadly and to other areas of the economy courtesy of the knock-on effects on income, employment, profitability, and asset prices. However, the consensus view is that this recession will be relatively mild. In the US there have been 12 recessions since the end of World War II, with an average peak-to-trough decline in GDP of 2.8% and a median decline of 2.4%. The two largest recessions have been the two most recent – the COVID-19 recession and the GFC in 2008-2009 – with most of the others having been in the 1-3% range (Chart 9).

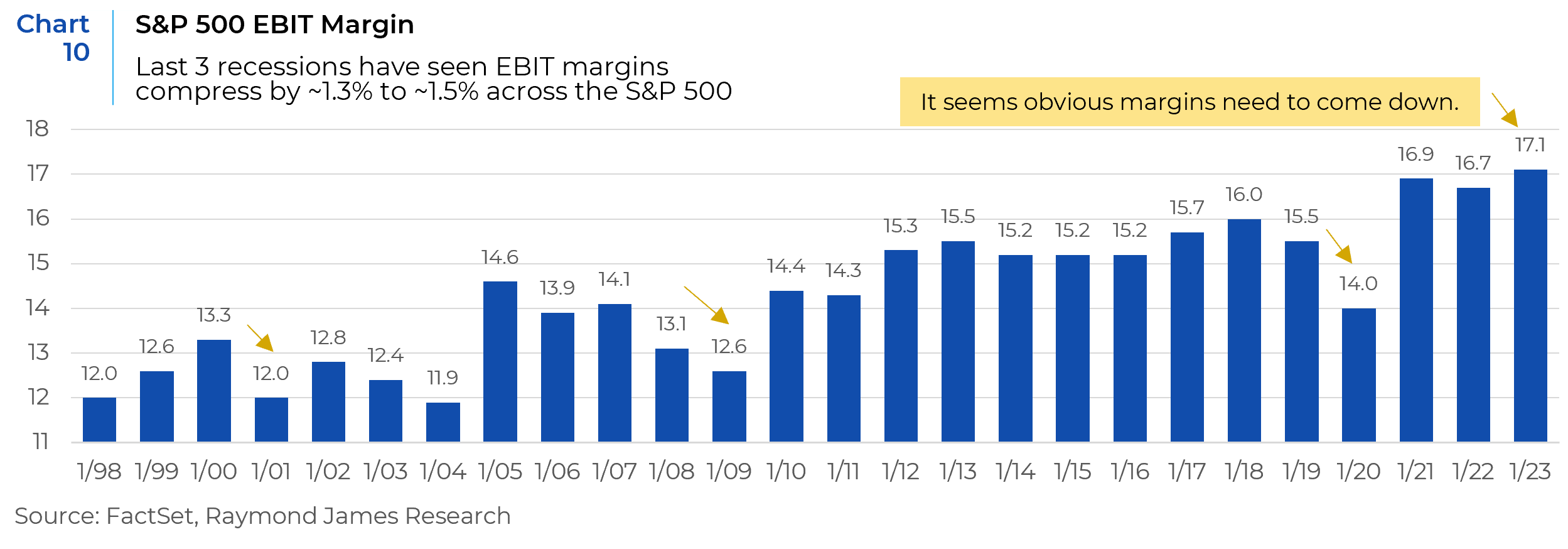

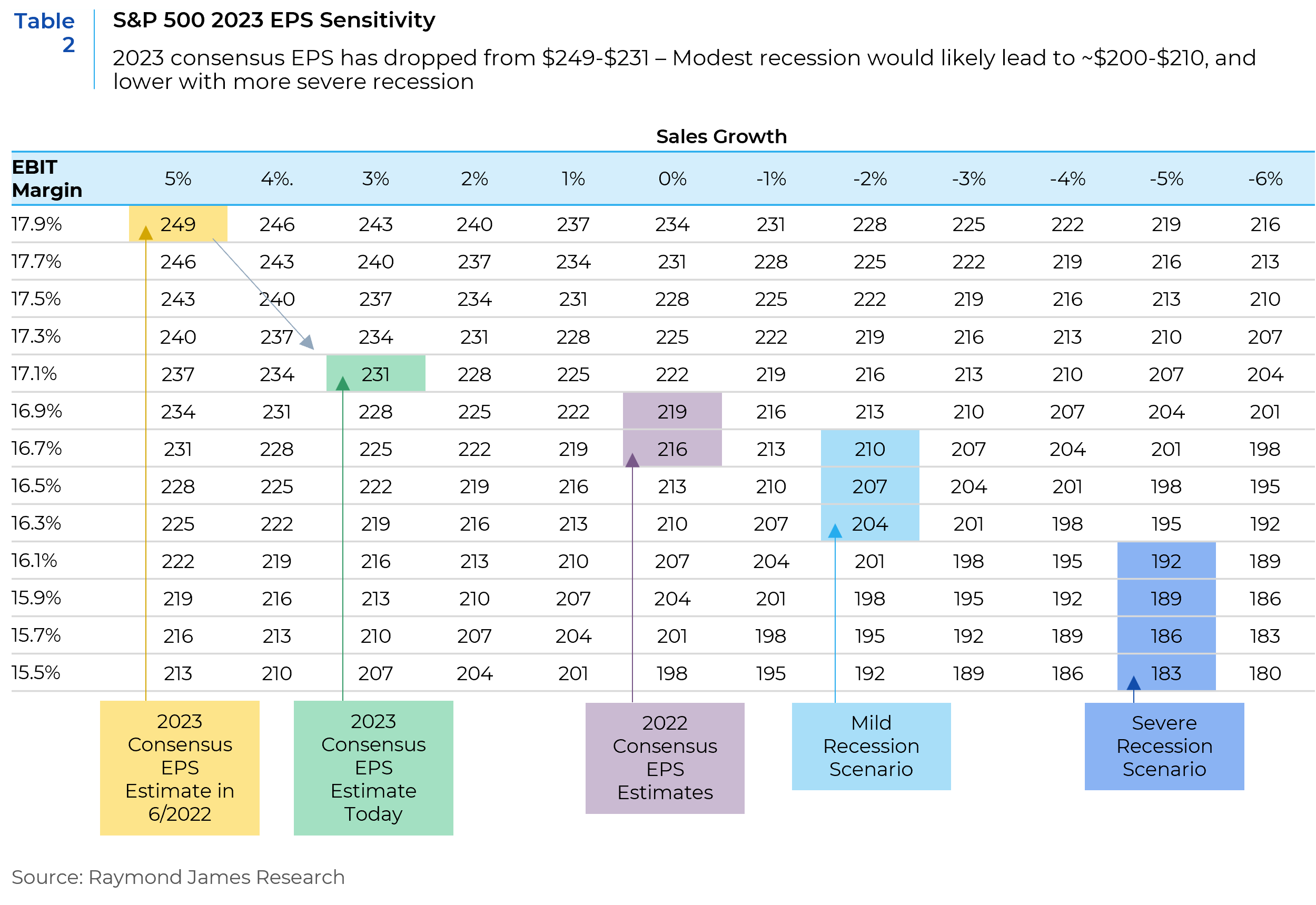

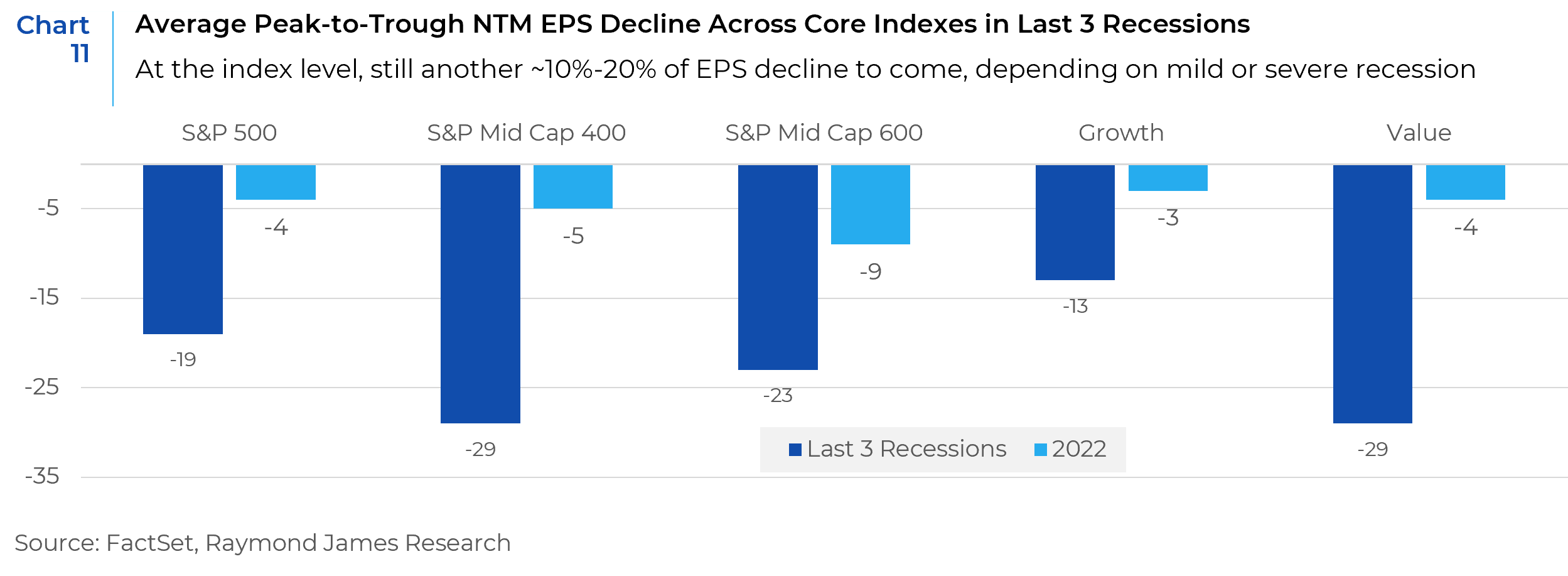

For many investors, a recession over the next 12 months is almost a foregone conclusion, but it is doubtful if the magnitude is fully priced in. It appears that given the state of labor markets, inflation will ease somewhat slowly, making central banks hesitant about cutting rates too soon or too fast. Equities, therefore, may have further to fall as interest rates climb further. Actual EPS growth and EPS estimates are both expected to trend downwards as 2023 progresses. EBIT Margins are expected to see more compression and the EPS estimates for the S&P 500 are likely to be cut further (Chart 10).

Outlook for Equity Markets

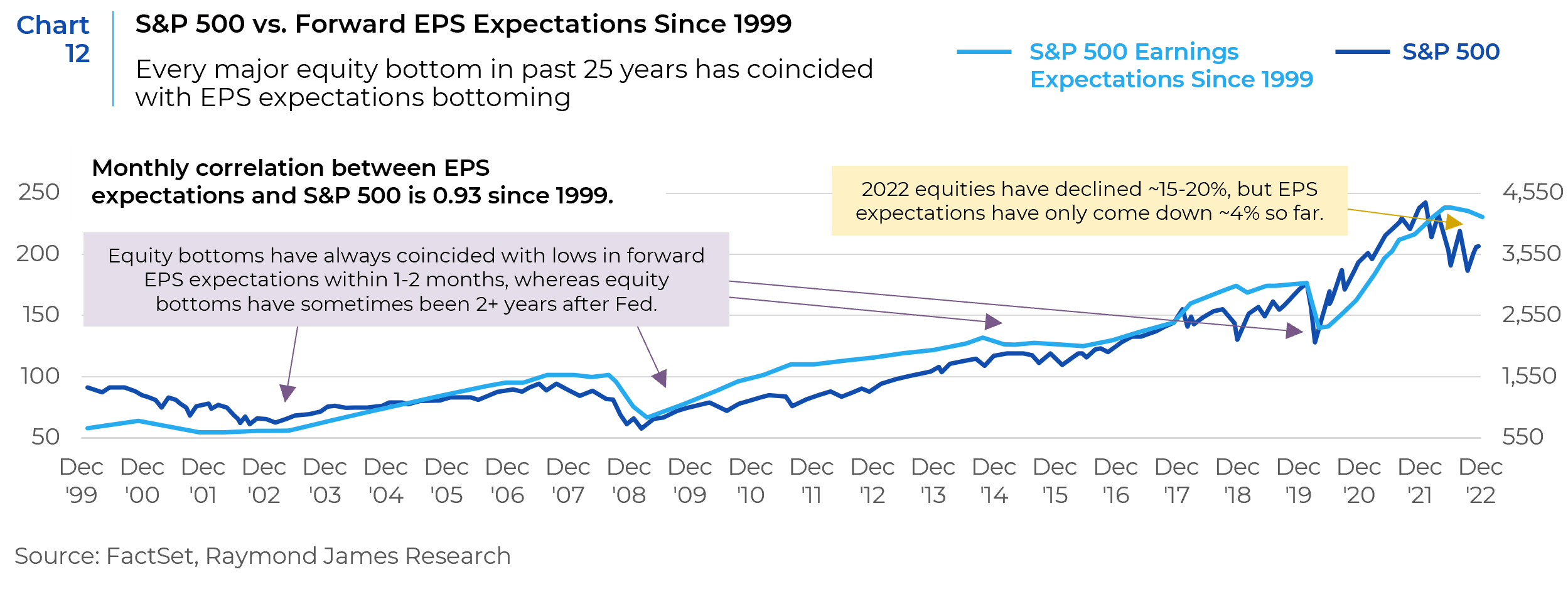

In 2022, the negative return to equities has been driven mainly by derating. We believe that equity earnings estimates do not fully incorporate the damage done to corporate earnings by the strong dollar and recent rate hikes. The last leg of a typical bear market initiated by an earnings recession has thus far been absent (Chart 12). Against the backdrop of inflationary pressures easing very slowly and leading activity indicators moving only gently lower, it will take time for remaining downside earnings risks to be recognized. However, once that happens, equity markets can take a turn for the better.

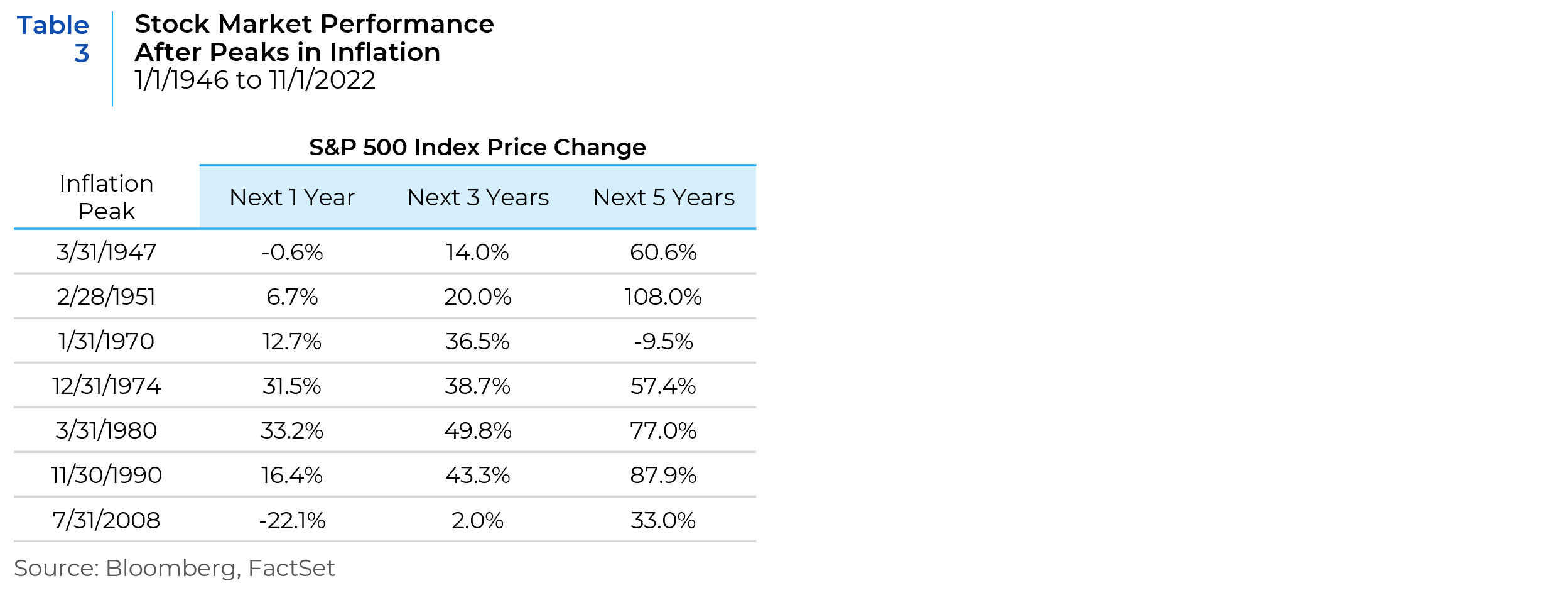

The risk of a recession remains high, as the Federal Reserve’s strategy of raising interest rates to choke off inflation may choke off economic growth as well. That said, if a peak in inflation has been reached and the magnitude of the expected recession is not too serious, historical precedent suggests that stocks are likely to be positive in the future (Table 3).

References: Barclays Research, BCA Research, Alpine Macro, RBC, Raymond James, Credit Suisse

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospects for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct, but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.