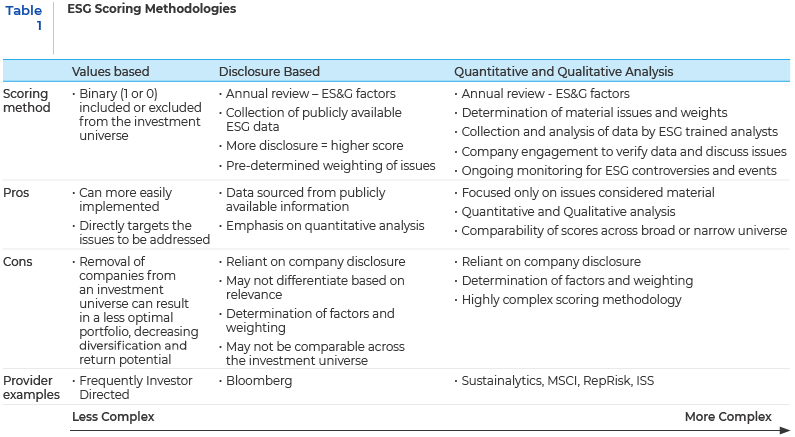

As ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investing trends have steadily risen, comparing ESG ratings and metrics has become more and more complicated. Over time the process has evolved from a values-based, often exclusionary approach in the 1970s, to the complex combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis employed in most of the ESG rating methodologies today (Table 1). The lack of regulation and the subjectivity used in calculating ratings has made the world of ESG a complex place.

Inconsistent Methods Across Rating Agencies

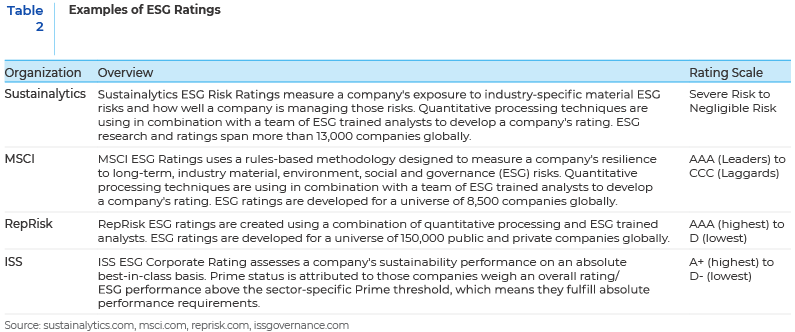

The increase in rating methodology complexity has resulted in a shifting of the responsibility for determining a company’s suitability for ESG investment from investors to the firms that are responsible for creating ESG ratings like MSCI, Sustainalytics, ISS, RepRisk, etc. Unfortunately, even if each organization used the same data, which they don’t, they all use a different methodology, metrics, comparison universe and weighting schemes. Therefore, how a company scores on ESG may vary depending on which organization is awarding the rating. Some of these differences may be small but in z and other techniques to incorporate more timely company specific ESG related news and announcements, particularly issues and controversies, into the rating process.

The bottom line is that comparing ESG ratings and metrics has become more complicated. Instead of too little information, investors may now find there is too much, but it is often conflicting, with few ways of objectively comparing results. Added to this is the issue that many ESG rating agencies disclose only a few of the indicators they evaluate, and few disclose the actual material impact of each indicator. As the ratings are not regulated and can be subjective, it is not unusual to get two different ratings from different agencies on the same company.

Many institutional investors are expressing a desire to move beyond using third-party generated scores, which often reflect not only a company’s reported data, but also the opinion of the analyst creating the score. Another issue with the scoring methodology is that ESG scores are often created using a one-size-fits-all approach. These inconsistent standards can result in scores varying widely among well-known ESG rating platforms. Many of these discrepancies result from not just the specific scores awarded to each component (E, S or G), but also how each platform chooses to weight each score to determine the cumulative ESG ranking.

Lack of Standardization in Disclosure Practices

One of the main issues for ESG-oriented investors and ESG ratings agencies is the lack of standardized data in the market. Businesses reporting their own ESG performance metrics are trying to satisfy increasing investor and stakeholder demand for more and better data. Meeting this demand is especially challenging given the plethora of reporting platforms and requirements and lack of consistent reporting standards for sustainability performance. As a result, different data points may be reported across companies in the same sector. Similarly, different data points could be reported by the same company from one year to the next. Another challenge with current ESG data sets is that some companies produce ESG information that is only partially measured and accounted for. For instance, one company may report the carbon emissions of its entire business, while another firm may only report the carbon emissions for its headquarters but not for its other locations or operations.

Policies and requirements for ESG disclosures can vary significantly. Currently, there are no standardized rules for ESG disclosures and there is no disclosure auditing process to verify reported data. The lack of consistency in the metrics for disclosure distorts the information available to both ratings agencies and investors. There are several reasons behind this lack of standardization. These include immaturity in accounting rules for the treatment of non-financial sustainability data, inconsistent reporting standards, the lack of regulation around ESG disclosures and their voluntary nature, lack of comparability across companies and industries, and the lack of appropriate technology for gathering, managing, and auditing the data.

Disclosure versus Risk Identification

Another issue with ESG rating systems is that they have often rewarded companies with more disclosures. It is possible for companies with historically weak ESG practices, but robust disclosure, to score in line with or above peers despite having more overall ESG risk. Moreover, a disclosure-based rating methodology provides ample room for companies to manipulate the disclosure process. Self-reported and unaudited sustainability reports are more likely to present companies in the best possible light, and may not alert investors of potential ESG risks. To incentivize voluntary disclosure, ratings agencies often reward disclosure itself more than whatever actual risk those disclosures might reveal. In this environment, a company with significant historical violations of ESG criteria may try to boost its ESG score by adopting more robust disclosure practices, despite having a higher overall ESG risk.

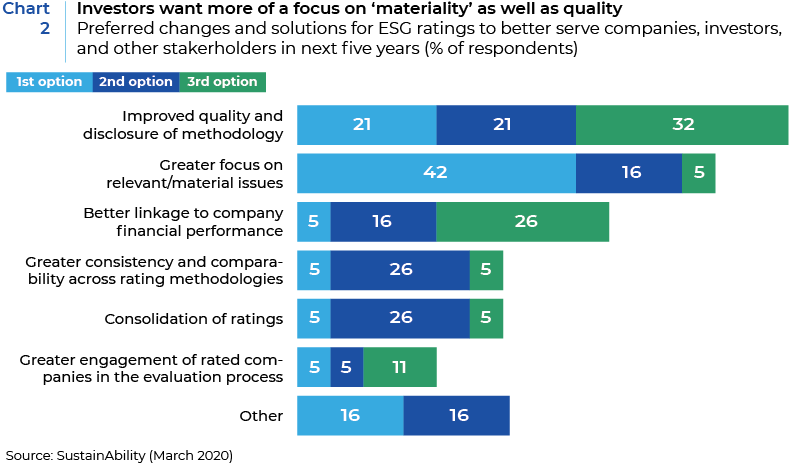

ESG ratings organizations are aware of the issues posed by users of their information and as such their ratings process continues to evolve. For example, although company disclosure remains the primary source of ESG data, ratings organizations are using techniques such as Natural Language Programming (NLP) and data scraping in an effort to incorporate more timely, independent, ESG related news and announcements, in the rating process. Also, a 2015 HBS paper titled the “Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality” highlighted the benefit of focusing on ESG issues that are material to a company’s future operating performance versus an emphasis on disclosure only. The primary ratings providers now incorporate a materiality assessment of ESG issues, often at the industry level, as the basis for their choice and weighting of factors considered in the construction of ratings. Although these improvements in evaluation techniques should result in a more robust and applicable rating it also adds another layer of complexity and further reliance on the views of the rating organization to determine what constitutes a material issue or factor and how it should be weighted.

Inherent Biases in ESG Ratings

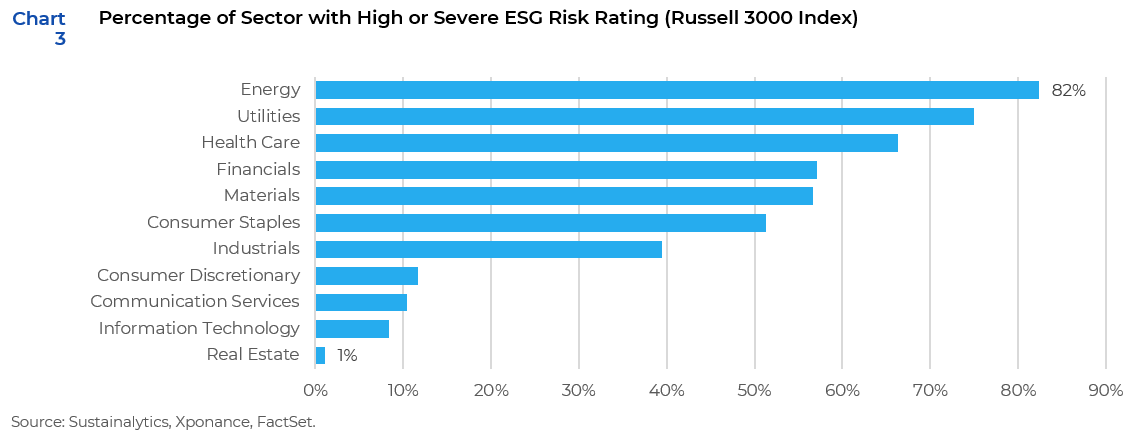

- Economic Sector Bias

Most ESG ratings incorporate an industry level comparison within their processes. However, when comparing companies across a diversified universe, due to the nature of their businesses, some industries and the companies that operate within them are more exposed to environmental and social issues, such as Energy, Tobacco, and Weapons Manufacturers. This can result in a biased rating for a company based on their industry, as opposed to company specific risks. Even if the ESG actions and behaviors of these companies are more positive than others, the inherent ESG risks in the industries they operate in will always add to the perception of these companies having higher ESG risk. The chart below provides an example of these sector biases using the Sustainalytics ESG risk rating.

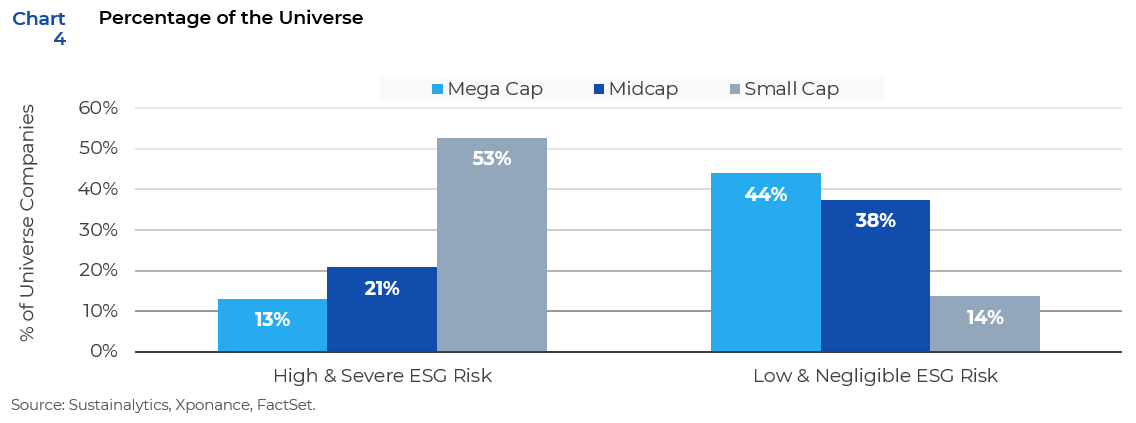

- Size Bias

Companies with higher market capitalization tend to be awarded ratings in the ESG space that are meaningfully better than lower market-cap peers, such as mid-sized and small businesses. By rewarding larger companies that have the ability to prepare and publish annual ESG disclosures, while penalizing those smaller companies that instead devote limited resources to fulfilling their ESG goals, ratings systems work in contradiction to their original purpose of providing accurate assessments of risk and opportunity. Instead of providing transparency, this bias shows how such ratings systems are not only subjective, but can also leave investors in the dark about the actual strength of a company’s ESG practices.

Practical Considerations

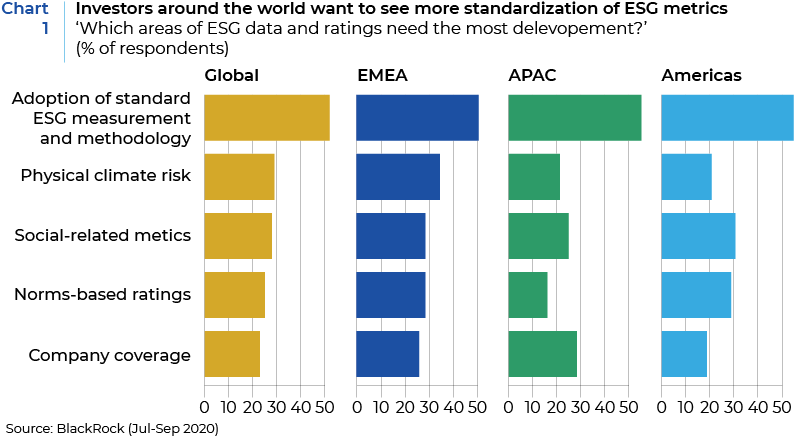

In the future, due to investor demand and regulatory requirements we expect that the quality and comparability of ESG data and ratings will improve. However, these improvements will take time. With that in mind, for now, ESG investors will be required to use the currently available data and ratings as effectively as possible in developing ESG investment strategies.

As we have highlighted, there is no standard ESG rating system. ESG rating provider methodologies are different, which can result in alternative ESG views of the same company. Although there has been a shift from disclosure only methods to a focus on material issues, the current ESG ratings are still dependent on non-standard, self-reported ESG data from companies and subjective input of the rating organizations. Therefore, investors need to make sure they look “under the hood” when considering the use of ESG ratings data and determine if the potential limitations of a methodology outweigh its benefit. The use of multiple ESG rating sources could be used to create a combination rating for a company to help identify outliers for additional analysis. However, in addition to the cost required to obtain multiple ratings, this approach does not remove the general limitations of ESG ratings and may just add an unnecessary level of complexity. In addition to being used on a standalone basis, ESG ratings can be used in conjunction with traditional, fundamental, measures found in financial statements to create a holistic view of a company’s suitability for investment.

For investors that want to emphasize specific ESG factors such as climate change, diversity and inclusion, human rights, etc. in their investment process, a broad ESG rating may not be appropriate. In these cases, investors will need to determine if this type of granular data is available from the rating organization or from another source.

For the sustainable investing movement to continue to grow, it’s critical that all parties work together on improvements in the quality, quantity, and accessibility of ESG data.

References:

Timothy M. Doyle, Vice President of Policy & General Counsel, ACCF, 2018, “Ratings That Don’t Rate, The Subjective World of ESG Ratings Agencies”

Leon Saunders Calvert, Head of Research & Portfolio Management, Refinitiv, 2021, “Understanding how ESG scores are measured, their usefulness and how they will evolve.”

Tim Mohin, TriplePundit, April 2021,” The Top 6 Barriers to Better ESG Data (and What To Do About Them)”

Brad Foster, Global Head of Enterprise Data Content & David Tabit, Global Head of Equity Data, Bloomberg LP, Pensions & Investments, April 2019,” Commentary: As demand for ESG investing grows, so too does the need for high-quality data.”

Mozaffar Khan, George Serafeim and Aaron Yoon, Harvard Business School, “Corporate Sustainability:First Evidence on Materiality”, 2015

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospects for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct, but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.