The world is undergoing a reordering of global markets that challenges most long-term capital allocation assumptions. Over the past three years1, we have consistently posited that ongoing inflation pressures and uncertainty would set a new lower bound for U.S. rates that is much higher than during the previous decade. The long-term structural drivers of these trends remain in place, and the market consensus (reflected in long-term interest rates) supports the view that the current political economy is likely to reinforce if not accelerate those pressures. As the current geopolitical and macroeconomic environment is reordering expectations of winners and losers in public markets, this is also true for private markets. In our recent dive into the shifting political economy in Europe, we shared our bullish 5–10-year outlook for European private equity (buyout and growth) returns.

In this piece, we will look into key structural differences within segments of U.S. private equity strategies (with an emphasis on buyout funds) that are likely to become critical return drivers in the coming years in the evolving macroeconomic environment. These key differences stem principally from different levels of leverage and relative valuation multiples that are likely to widen the dispersion of realized distributions between large and mid/small funds for the foreseeable future.

Losing Leverage

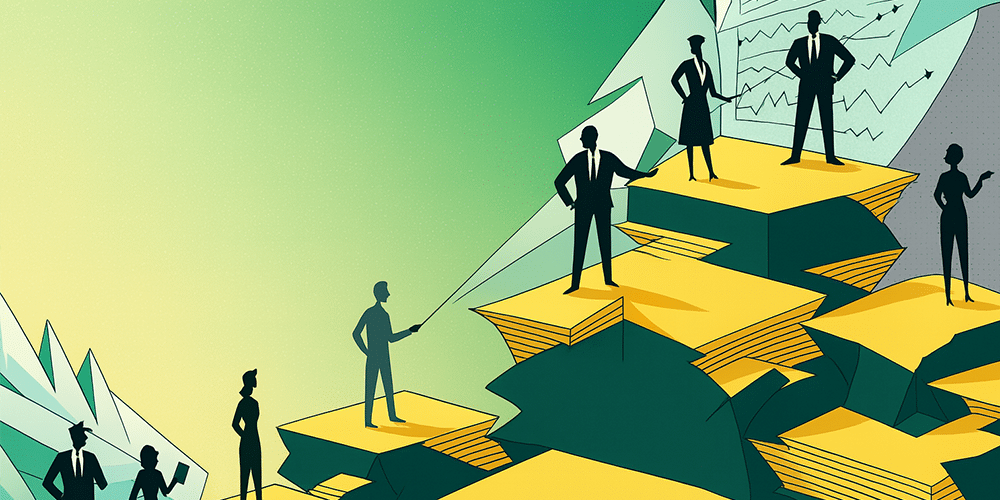

The classic playbook for buyout strategies, combining operating leverage through management improvements and/or additional scale with financial leverage through (comparatively) cheap debt to drive higher equity returns, is clearly under pressure amid higher rates. But this stress is especially acute for larger buyout funds given their historic reliance on greater levels of leverage for their underlying portfolio businesses. Long duration data from 2000-2020 (see Chart 1) shows that average leverage multiples have been 50-100% higher for larger buyout companies, which remained true in the post-GFC period data (see Chart 2).

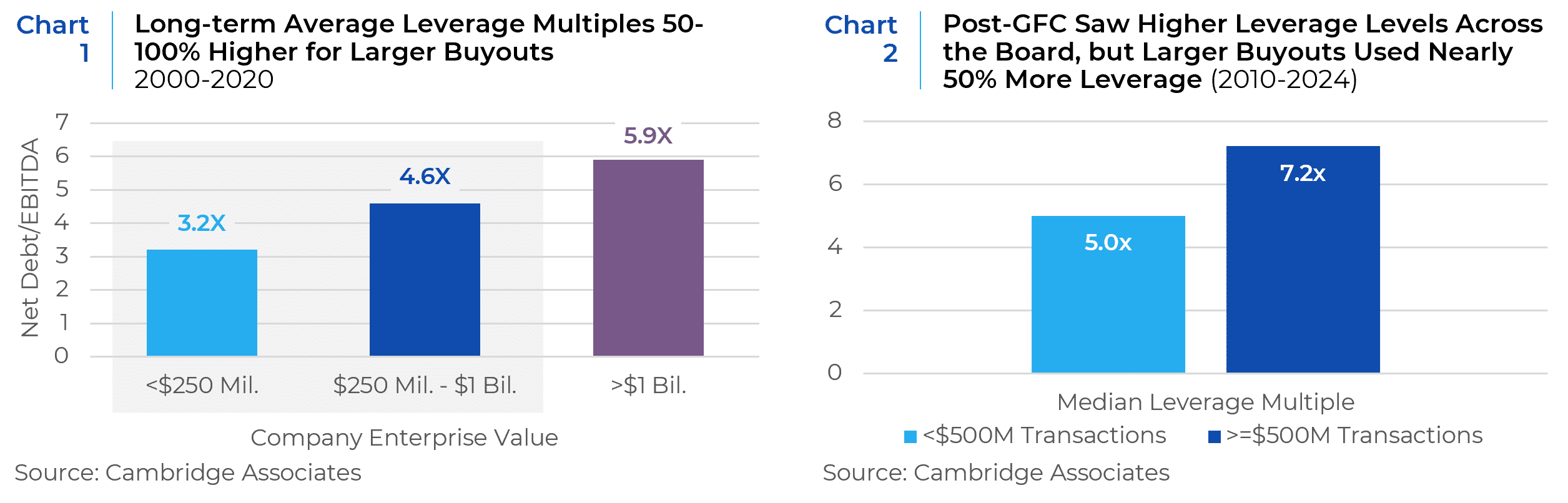

During the post-GFC period in particular, rates were not only consistently low, but the growth in private credit created an additional supply of debt to buyout GPs. But with policy rates now 400bps+ higher and private credit AUM growth slowing2, the cost of leverage is taking its toll on private equity returns. Not only do higher levels of leverage generate additional costs for sponsor-backed enterprises, but in this environment of uncertainty and widening spreads, it also imposes substantial enterprise risk. This is why exits in highly levered companies have collapsed in recent years, impairing distributions and LP returns, especially from larger funds (see Chart 3).

Valuing Valuations

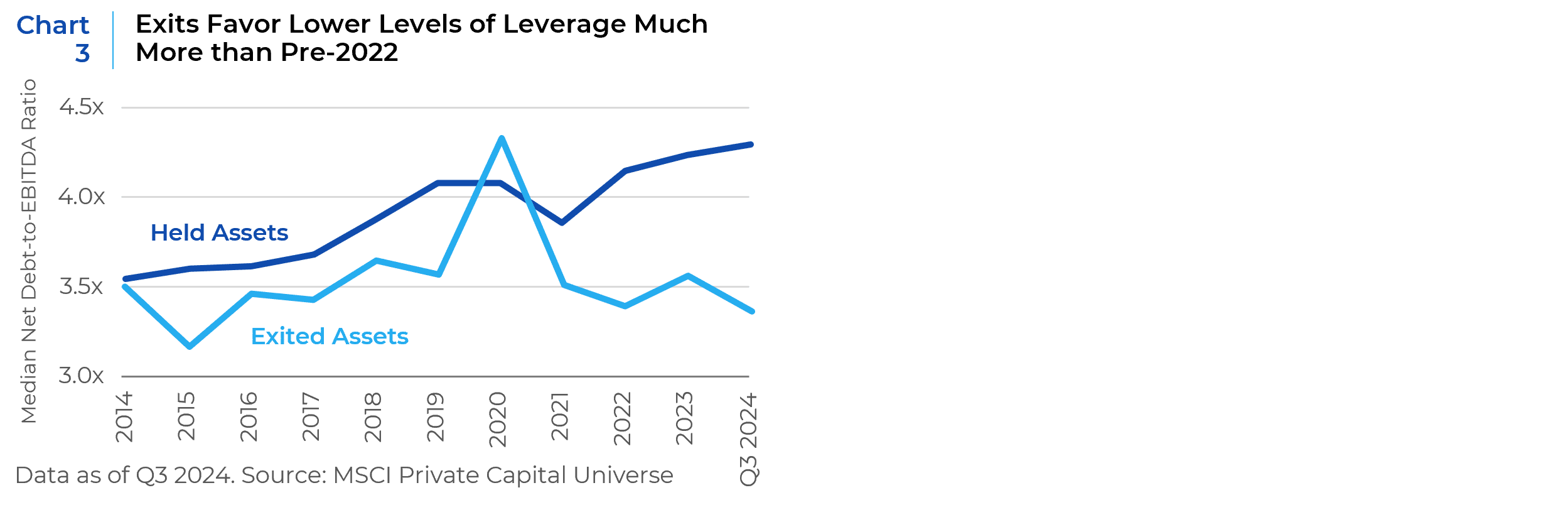

The costs and appetite for leverage are not the only factor that has changed in the past three years. For decades, median realized private equity valuations routinely exceeded those of unrealized valuations. Thus, LPs could count on the marks being used for most of their private investments to be realizable minimums in forthcoming exits. But the rate and market shocks of 2022 have led to a breakdown of this relationship as well. As Chart 4 shows, the last several years of private equity exit valuations have fallen not only significantly short of unrealized valuations but saw two years of absolute valuation declines.

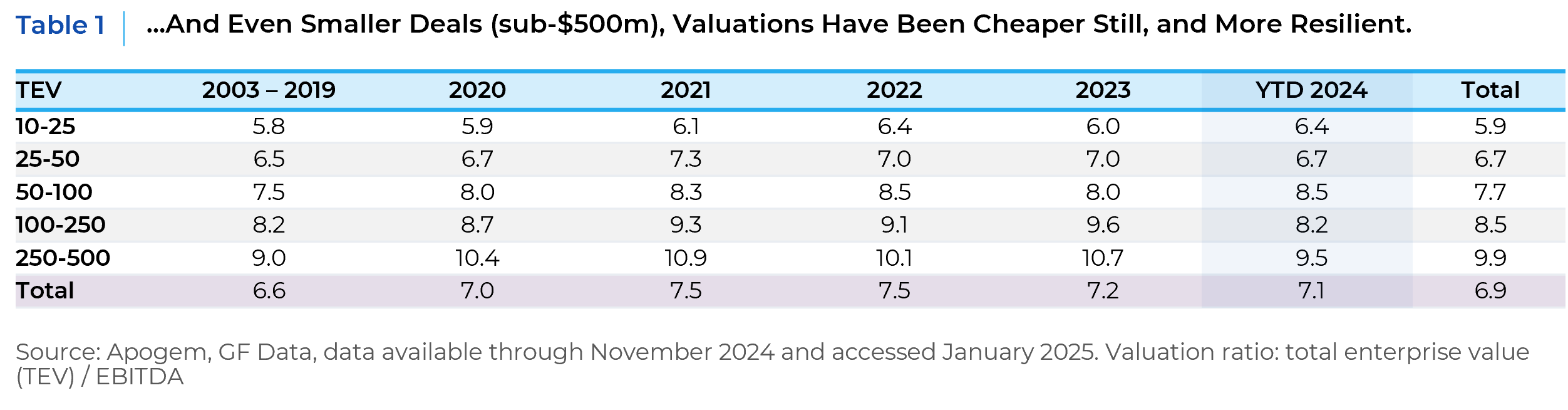

While this pressure on valuations is a market-wide phenomenon, it will be felt most acutely by the largest funds who (as a group) have traditionally paid much more for their assets. Chart 5 shows that small buyouts (defined as sub $1bn companies) have consistently enjoyed a material discount in the market to their larger peers. Moreover, valuations are consistently more attractive for lower deal sizes, while valuations for the smallest GP’s buyouts have already largely recovered relative to the 2021 peak (see Table 1). Historically, these higher valuations were partly justified by higher levels of profitability for larger firms that were on average 3-5 percentage points higher.3 But Chart 4 suggests that this historical profitability advantage has either diminished over the past two years4 or is now insufficient to compensate investors for higher valuations in the new rate environment.

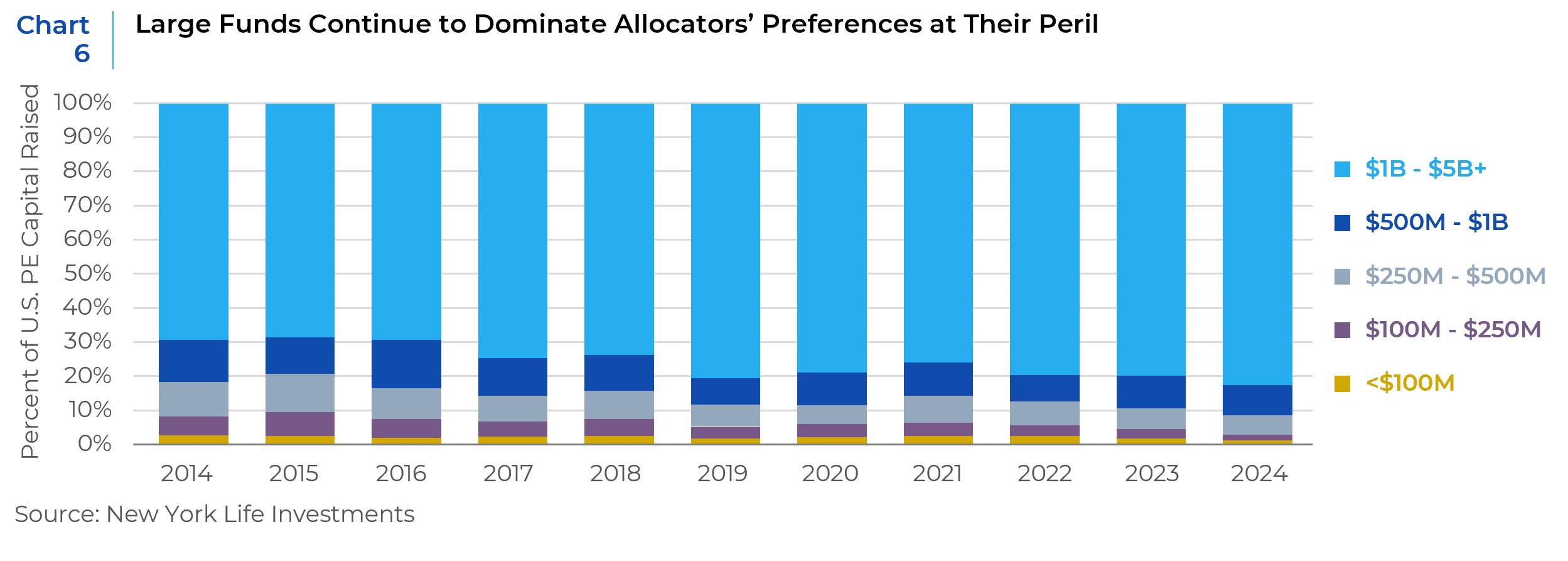

Despite these challenges, the largest buyout funds have continued to dominate the fundraising landscape (see Chart 6).

Passing Fad or Passing the Baton?

While it is difficult to predict if the heightened sensitivity to leverage and higher valuations will hold for the next decade, we think there is good reason to think it is the path of least resistance, at least as it applies to U.S. buyouts. As we have written about previously, we believe the outlook in America is for higher rates for longer given the abundance of inflationary pressures affecting the U.S. economy including reshoring, tariffs, AI-driven energy demand, policy-created labor market shortages, and fiscal largesse that increases the supply of U.S. government debt the market needs to absorb. Perhaps even more important is just the opportunity cost of capital. More than any time in the past 10 years, private equity faces new competition in securing limited space in allocators’ portfolios from private credit, resurging macro and commodity/CTA strategies, as well as overseas assets (buoyed by a medium to long-term outlook for USD-weakness – whether structural or cyclical). Coming on the heels of a period of depressed exits and distributions from private equity, investors are likely to maintain their newfound selectivity within the asset class for years to come. With structurally higher interest rates, compressing valuations, and now a potential repricing of U.S. risk premia by foreign investors too, we feel that allocators may be better served by focusing their private equity investments much further down the size spectrum than they have before.

In our next discussion, we will look at the empirical evidence for whether smaller funds have delivered superior returns and distributions, and what the outlook for any historical trends in those return patterns may look like going forward in this new investment landscape.

References

https://www.xponance.com/the-precariat-are-still-mad-part-iii-how-should-investors-play-the-next-4-years-it-depends/

https://www.xponance.com/laboring-under-pressure-are-labor-supply-trends-breeding-long-term-stagflationary-conditions/

https://www.xponance.com/the-view-from-the-top-what-the-markets-look-like-at-a-potential-top-of-the-rate-cycle/

https://www.xponance.com/the-great-rebalancing-q1-2023-market-outlook/- Pitchbook US Private Credit Monitor. May 2025.

- https://www.cambridgeassociates.com/en-eu/insight/us-private-equity-looking-back-looking-forward-ten-years-of-ca-operating-metrics/

- Reliable data on margin levels for the past 2 years by company size could not be found.

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospective clients for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.