“These are the times that try men’s souls; the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

– Thomas Paine, The American Crisis, 1776

In the winter of 1776, Philadelphia and the entire rebel American cause were on the verge of death, Washington’s troops threatened to desert him, and the revolution was still viewed as an unsteady prospect. In order to bolster their morale and resistance, Washington ordered Thomas Paine’s Crisis paper be read aloud to the troops of the Continental Army on December 23, 1776. Three days later, the troops won their first victory in the Battle of Trenton, a pivotal turning point in the Revolutionary war.

Whereas in 1776 the very existence of our nation was in the balance and many would die to defend it, today we face the twin (and related) existential threats of a deadly coronavirus and an alarming entropy in the social bonds and political norms that have undergirded America’s democratic ideals.

History teaches us that financial assets and markets can survive and indeed thrive under different political systems (see China and Thailand for example), but social unrest and instability are their common and universal kryptonite. The global lockdowns in response to this coronavirus led to the sharpest economic downturns in recorded history and, by disproportionately threatening both the lives and livelihoods of the most vulnerable segments of society, have kindled the already white-hot political embers of hyper-partisanship and grievances that now characterize our political landscape. When combined with long-standing racial disparities, these tensions have erupted into mass protests and disturbing acts of violence by a few bad actors that are more motivated by opportunism or anarchy than racial justice. On top of that, geopolitical risks have been rising in the Mediterranean (between Greece and Turkey), the Caucasus (i.e., the war between Azerbaijan and Armenia), in Asia (South China Sea and between India and China) and in Great Britain. In the U.S., we are in the midst of an historically contentious Presidential election.

In these times of heightened anxiety, our firm-wide investment strategy discussions have invariably turned to discussion on risks that keep us up at night as investors (and citizens). Based on polling among our investment professionals, we deemed the most immediate market relevant risks to be:

- The risk of a contested election and ensuing civil unrest

- Economic lockdowns in response to a third wave resurgence of the coronavirus

- Fiscal policy uncertainty

In a subsequent research note, we will discuss longer term risks, such as the growing imbalances in financial assets with the alarming dominance of a handful of technology companies that are increasingly facing regulatory scrutiny; geopolitical powder kegs in the Caucasus, the South China sea and other areas; and the undiscounted threat of inflation levels (more likely, stagflation), once the coronavirus threat is behind us. This would challenge current DCF models that are flattering risk assets and the correlation assumptions underlying asset allocation models.

Any one of the three risks discussed in this research note could cause a material negative shock to risk assets. Their combination warrants, at most, a neutral allocation to riskier assets for the short to intermediate term. For long term focused investments these short-term risks, though material, are unlikely to derail the positive cyclical backdrop for non-U.S. assets and cyclical value stocks that we outlined in our prior research note (see our Q2 2020 Market Outlook). Over the next year to 24 months, we continue to believe that cyclical assets and sectors will be buoyed by historically low discount rates, continued fiscal accommodation globally and the discovery and dissemination of a vaccine for the coronavirus, which surveys of medical professionals suggest is becoming increasingly likely. In this scenario, the U.S. dollar would be expected to resume its slide, cyclical sectors and non-U.S. assets would resume their August outperformance, particularly if there is a Blue Sweep.

Forecasting and managing risks require a combination of analytic rigor, humility, and imagination. Unfortunately, the human imagination is a poor tool for judging risk. We typically excel at responding to the crisis that just happened, as we naturally imagine that whatever just happened is most likely to happen again. We are less good at imagining a crisis before it happens—and taking action to prevent it. Another way of putting this is: the risk we should most fear is not the risk we easily imagine. It is the risk that we don’t imagine. Our crystal ball is, of course, no more clairvoyant than that of others who have attempted to wade into the murky waters of financial forecasts for inherently non-linear events. Consequently, we have settled on what we believe to be a reasonable and straightforward framework in which each risk is evaluated relative to: a. its likelihood; b. whether it is already discounted by market participants; and c. its likely effect on financial assets. In doing so, we have attempted to stretch our individual imaginations by harnessing the perspectives of all three of our investment platforms, and the multiple backgrounds and perspectives housed in our firm-wide investment team.

1. The Risk of a Contested Election and Civilian Unrest

Despite a meaningful lead in national polls by former Vice President Biden over President Trump, the next President of the United States will be decided by the outcome in approximately 13 states. Moreover, mail-in ballots are estimated to account for at least one-third of total ballots this year vs. 10% in 2000, the year of the last contested presidential election between former Vice President Al Gore and then Governor George W. Bush. Currently 13 states, including the swing states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, do not tabulate mail-in ballots until election day. Moreover, recent rule changes in North Carolina and Wisconsin mean that ballots received after the election (but post-marked before it) are still accepted. The larger concern is that in a number of battleground states President Trump may appear to have won on election night but, after mail-in votes (that appear to be predominantly Democrat supporting) are counted over the following days, the states’ electoral votes will move into the Biden camp. Additionally, in some states (for example, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin), the governorship and the legislature are controlled by different parties, and each might send a separate slate of electors to Congress on January 6th. The procedures for what happens then are complicated – but the dispute would invariably drag on and the ultimate result will be considered illegitimate by a sizable percent of the U.S. population.

What Are Investors Discounting?

Betting markets are increasingly discounting a so-called Blue Wave (Chart 1 and Chart 2). As Vice President Biden’s lead over the President has increased, particularly in key swing states, market participants have accordingly been discounting the risk of a contested election. According to a survey of investors and corporate clients by Evercore ISI earlier this week, 76% of respondents anticipated clarity on the winner within a week of Election Day, up from 63% two weeks ago (Chart 3). Accordingly, options markets have steadily reduced event risk priced around the U.S. presidential election across a wide range of global assets (Chart 4).

While a clear election outcome on November 3rd would obviously reduce the risk of a contested election, we believe that the market may be underappreciating the risk of civil unrest that even a week’s delay in determining the outcome may foster. In other words, the market relevant risks are not the fact of a contested election, but the second and third order adverse responses to it.

Even if current polling suggesting a Biden win and/or a Blue Wave prove to be accurate, three factors could exacerbate the risks of civil unrest:

- Presidential rhetoric that has consistently casted aspersions on the legitimacy of the electoral process. The President has been particularly focused on undermining the authenticity of mail-in ballots (which received political wisdom posits to be more Democratic) and casted aspersion on the likely possibility that the results of the election will be determined well after November 3rd, as we await the tabulation of mail-in ballots. The last time the U.S. faced a disputed election, Al Gore’s acceptance of the Supreme Court’s ruling, which led to the election of his political opponent, helped to heal the hyper-partisan fissures that could easily have devolved into a dangerous cascade of partisan recriminations. By contrast, President Trump’s rhetoric raises the risk that he would attempt to delegitimize the results, in today’s seemingly more dangerously partisan environment. When asked in the first presidential debate whether he would commit to a peaceful transfer of power, Trump responded: “We’re going to have to see what happens. You know that I’ve been complaining very strongly about the ballots, and the ballots are a disaster”.1 Another non-negligible risk (which is not being discounted) is that if defeated, a frustrated President Trump could easily dish out negative surprises, particularly on China relations, until he leaves office on January 20.

- More widespread electoral disputes and broader public focus. Relative to the 2000 election, where the focus was on perceived voting irregularities in one state, the geographical footprint of disputed states this time around could be broader. Moreover, a contested election today would play out well beyond the echo chamber of political, media and legal insiders in 2000 to a broader segment of the population, whose anxiety may be more heightened by both the pandemic and any manifestations of recent high-profile threats of an armed response by certain radicalized groups.

- The extreme hyper-partisanship of the current media broadcast and social media landscape. Unlike the 2000 election, many Americans receive their news and perspective on current events through partisan echo-chambers that are remarkably divergent. Should there be a disputed outcome, these media outlets could exacerbate each party’s suspicions of being “cheated”.

With respect to anticipated market outcomes, history provides few useful analogs to estimate the response of financial assets. Contested presidential elections that disputed the legitimacy of the outcome have only occurred twice in U.S. history: the 1876 election between Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, and the 2000 election between former Vice President Al Gore and then Governor George W. Bush. Unfortunately, the 36 disputed days of the 2000 election, (when the S&P 500 index fell by 5%, non-U.S. equities fell by 3.2%, ten-year treasury bonds rose by 3.45% and the U.S. dollar slightly declined), are an imperfect analog. As noted previously, Al Gore’s acceptance of the court ruling curtailed both political uncertainty and market volatility. Moreover, bond yields in early November 2000 were above 5% vs. today’s level of .74%, thus theoretically providing less asset protection. On the other hand, despite the strong post March rally in U.S. share prices, P/E ratios today are slightly lower (22x earnings vs. 27.6x earnings in early November). For investors that have the flexibility, safe haven currencies, options and futures are likely to provide a hedge against such volatility. While richly valued, gold is also typically a haven in times of uncertainty; however, it also has an inverse relationship with the countercyclical U.S. dollar and real yields.

2. Third wave resurgence of the coronavirus

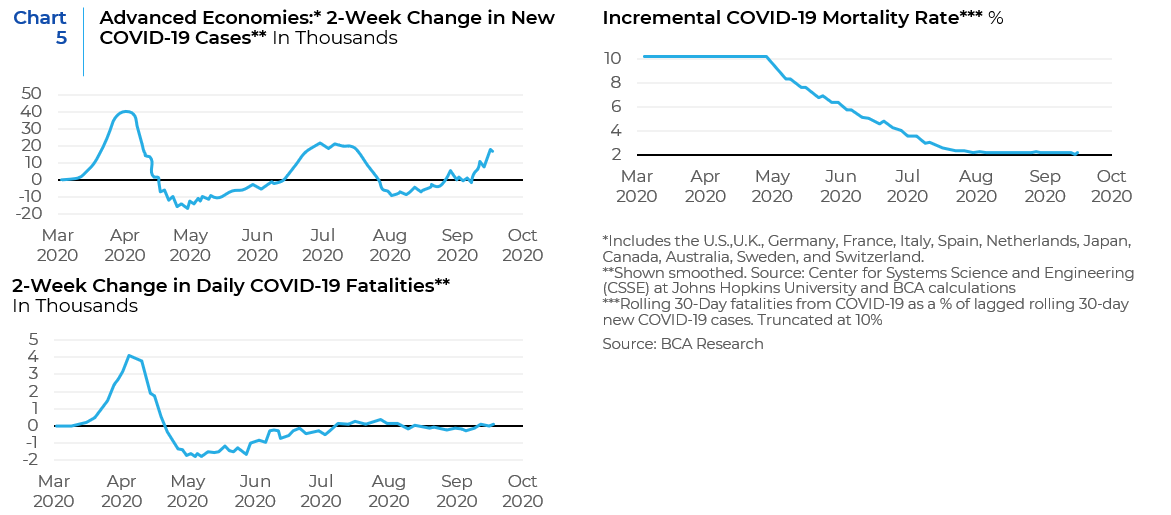

The pandemic appears to be worsening again, with a third wave of COVID-19 cases in the U.S. and a second wave in Europe and Asia (Chart 5). Moreover, as the northern hemisphere enters into the winter and flu season, many epidemiologists are warning of a so-called “twin-demic”. However, as noted in our prior quarterly note, because mortality rates are substantially lower than they were earlier in the year (likely due to a combination of improved therapeutics, reduced viral load due to more widespread mask wearing and because those infected are disproportionately younger), government leaders will be less likely to impose the generalized global lock-downs that stalled all but digital activity earlier this year. We do however expect a series of localized and repeated lockdowns that will slow the recovery in consumption and would be likely to increase the number of job layoffs and permanent business closures.

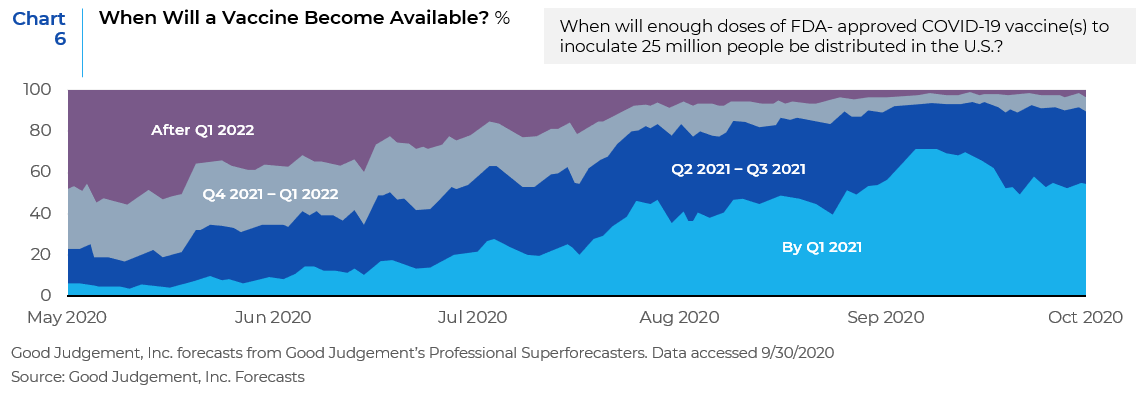

As the recent setbacks with the vaccine trials for both Eli Lilly and Johnson & Johnson show, the development of a vaccine is inherently complex and uncertain. That said, public health experts are demonstrating increasing optimism on the likelihood of a vaccine in 2021. According to the Good Judgements survey over 80% expect the availability of a vaccine by Q2 2021 (Chart 6).

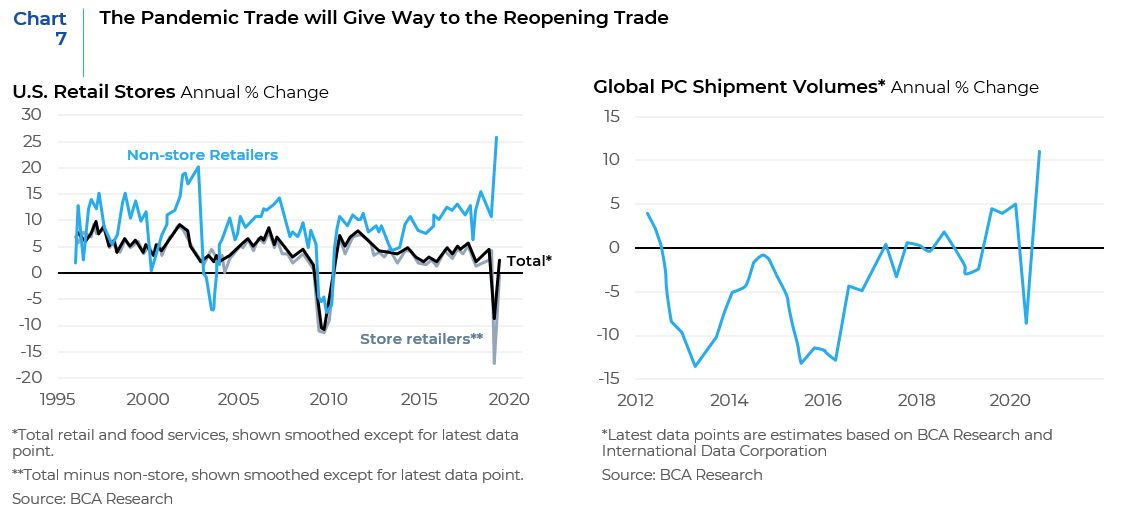

Investment implications: The pandemic will continue to weigh on physical service sectors such as the airline, hospitality and retail sectors. However, these sectors are already at bombed valuations and the marginal growth in digital sales will likely level off as the pandemic brought forward sales and hastened penetration into new markets, households and businesses. Moreover, the combination of rock bottom interest rates and supportive fiscal support will fuel a powerful reopening trade for non-digital or physical economy sectors.

There are two risks to investors. The first is that cases climb significantly, a third wave gathers full steam, and investors dramatically de-risk their portfolios (as many did in March). As discussed above, we believe that the current environment should lead investors to buy on the inevitable market pullbacks that will occur and to shift their orientation towards sectors that have been most impaired by the pandemic. This would mean a shift towards physical production sectors, most of which are value-centric, such as commodities, industrial and financials, that would disproportionately benefit from an accommodative policy environment and an easing of lockdowns (Chart 7).

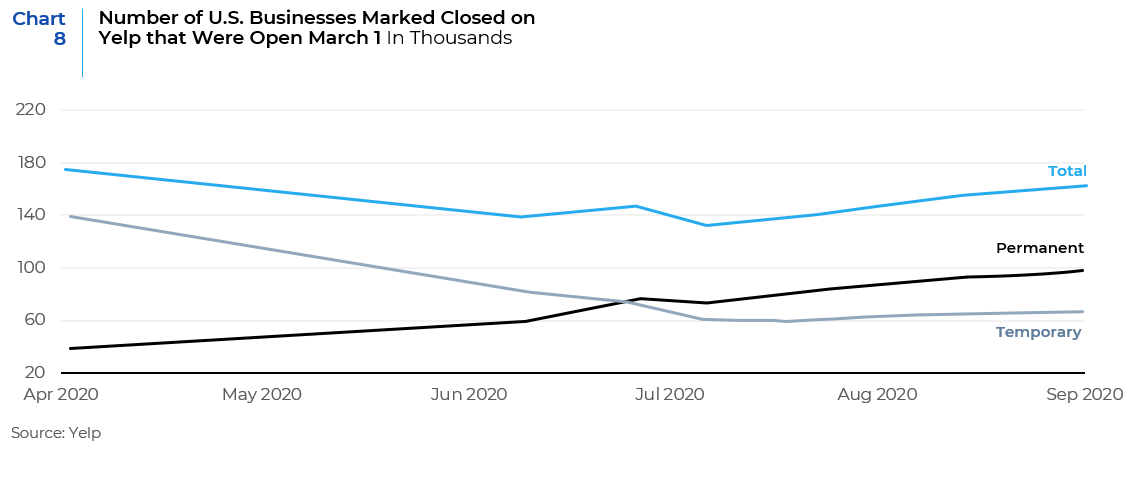

The second underappreciated risk arises from the level of supply destruction caused by the global lockdown is more long term. In 2019, 17 retailers filed for bankruptcy protection in the U.S.; so far in 2020, 27 have filed. More than 73,000 restaurants have closed permanently in the U.S., according to Yelp, and estimates of permanent closures range from 25 to 40% of all U.S. restaurants (Chart 8). The recovery in the real economy from the 2008 Great Recession took around 8 years. We believe that the recovery time in response to both the first global lockdown and likely ongoing localized lockdowns will be longer and more tenuous. This likely long-term loss in supply or disruption of supply chains, combined with historic levels of fiscal accommodation (which relative to the response to the 2008 recession, is meaningfully larger and disproportionately focused on buttressing consumer demand); a global shift towards more populist policies in response to growing income inequality; as well as increasing trade deglobalization, could lead to an upside surprise in inflation in the next three to five years.

3. Fiscal policy uncertainty

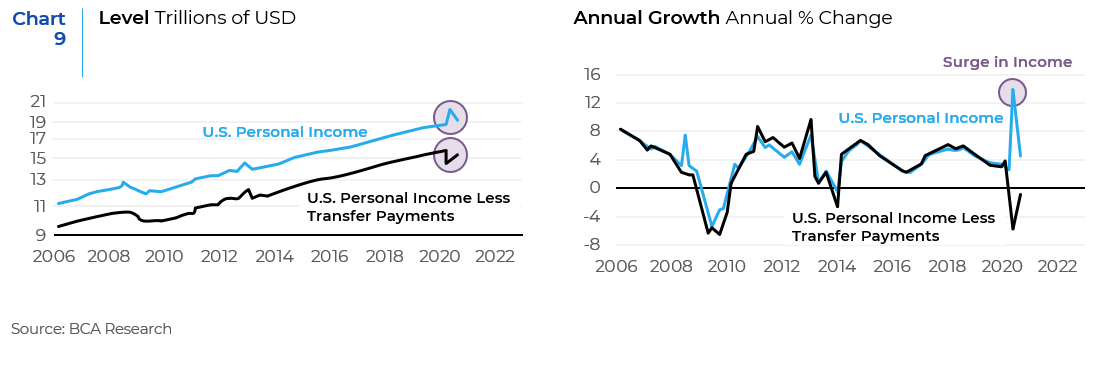

With the Fed pursuing “maximum employment” and average inflation targeting, fiscal policy will continue to be critical to the fight against COVID-19. Governments have subsidized wages, mailed checks to households and guaranteed loans for business. In the U.S., the CARES Act has propped up household income and kept domestic demand higher than it would have been otherwise (abating the economic fallout from the coronavirus lock down by approximately 5% of GDP) (Chart 9). The Act’s renewal is thus increasingly seen as vital for a sustained recovery; which is why when the fiscal spigots were at risk of drying up due to stalled negotiations between House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the administration, risk assets stumbled in mid-September.

Failure to renew the CARES act could easily cause the nascent recovery to morph into a double-dip recession, especially if Washington is stuck in a gridlock next year. While this would cause a narrowing of the U.S.’s ballooning trade deficit, it would be debilitating for the domestic and global economy as well as for asset prices. Therefore, despite the recent drama, more help from Washington will come. Moreover, both presidential candidates have indicated their support of additional pandemic-related fiscal stimulus. The questions are not if, but when, how big, and with what policy mix.

The presidential and congressional elections provide another source of fiscal policy uncertainty in that the stark differences between Democratic candidate Joe Biden’s and President Donald Trump’s campaign platforms will have material implications for key market segments. Understanding the platforms of each presidential candidate is necessary but insufficient to estimate its market impact; as the results in the Senate and the state of the economy when the new presidential term begins will also determine the likely size and timing of fiscal policy to come. In a Blue Sweep, for instance, with a Democratic president and Congress, if the economy is still struggling, we could easily see spending prioritized and tax hikes moderated and/or postponed.

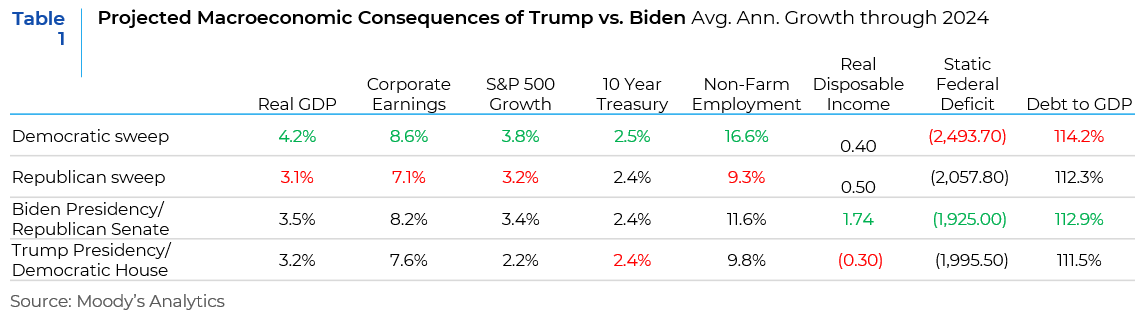

Table 1 below delineates the projected macroeconomic consequences of Trump vs. Biden presidency under both clean sweep (for either party) and divided government scenarios based on research conducted by Moody’s Analytics.

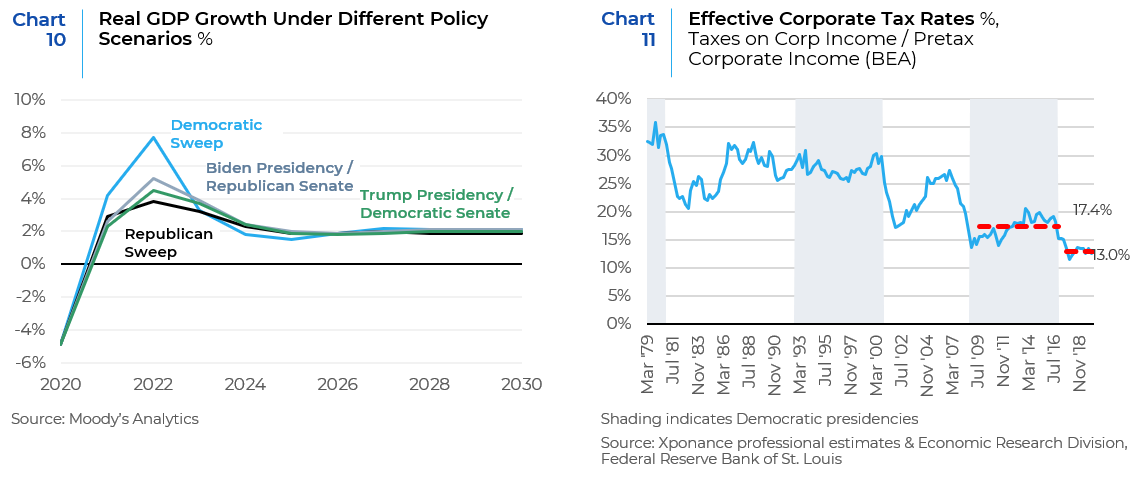

These projections suggest that Biden’s aggressive fiscal program, particularly in the context of a Democratic sweep, would be expected to boost aggregate demand above other political configurations. Most of the growth would come early in Biden’s term (Chart 10) which would in turn boost before tax corporate earnings, stocks and bond yields. A Blue Sweep would likely lead the U.S. towards a more redistributionist direction, especially with respect to taxes and healthcare. This is in part why non-farm employment is the variable with the greatest difference relative to either a Republican sweep or a split government with Trump as the president, whilst disposable income is lower. Biden’s proposal to increase capital gains taxes and corporate taxes to 28%, whilst limiting certain deductions would be expected to negate some of the expected higher top line growth in corporate earnings. The Trump administration’s tax cuts reduced average effective corporate tax rates by approximately 4.4% (Chart 11); a benefit which would clearly be threatened by a Blue Sweep.

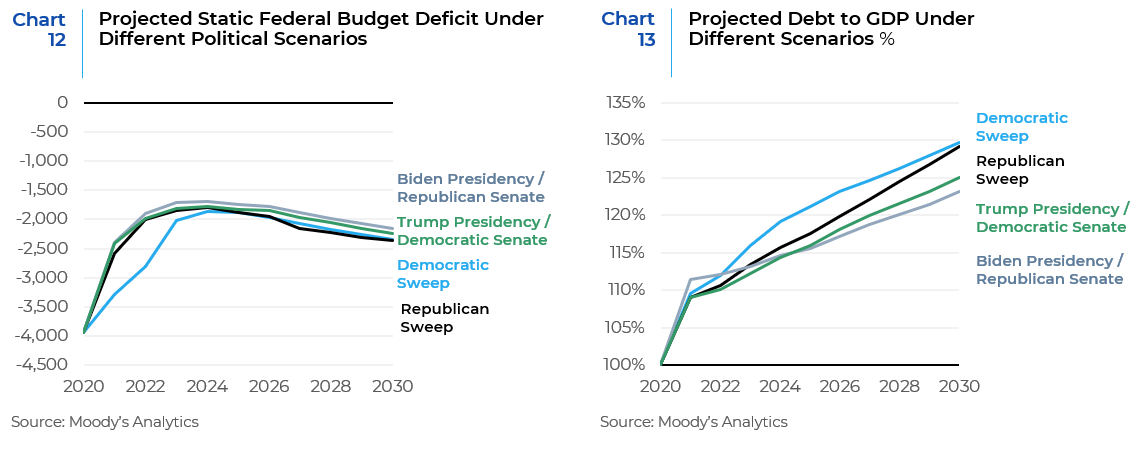

The most fiscal restraint would be expected from the combination of a Biden Presidency and a Republican Senate. Biden’s more aggressive fiscal policies would also result in a higher deficit and debt to GDP ratio, particularly in his administration’s early years. However, over the full term and even more so over a 10-year period, the differences between a Democratic vs. Republican sweep are immaterial (Chart 12 and Chart 13).

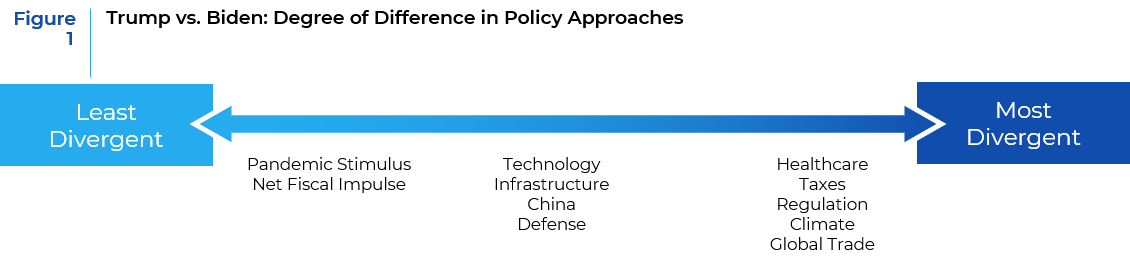

Below, we depict the salient policy differences between a prospective Biden presidency vs. an incumbent Trump presidency (see Figure 1).

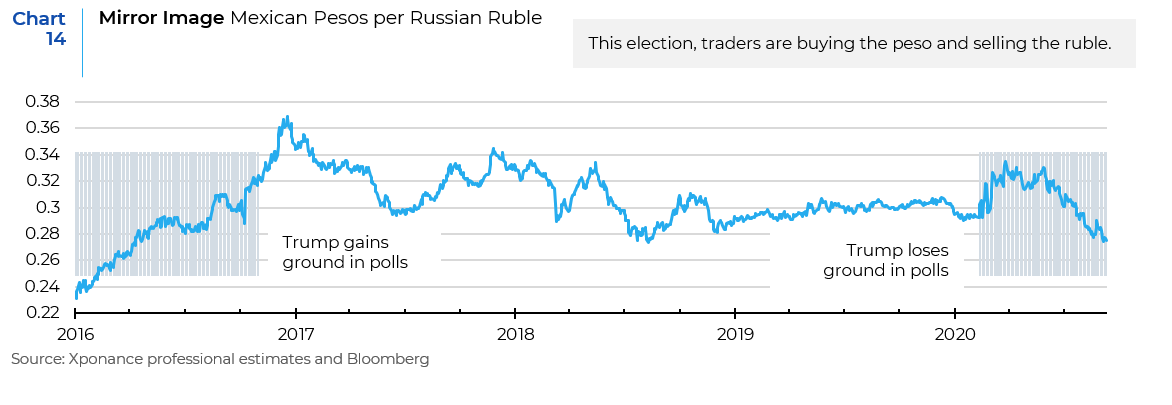

A divided government would constrain Biden’s more redistributionist policies and any further tax cuts to corporations by Trump. A Trump presidency would represent a doubling-down on its current policy focus, leading to lower taxation and an even more assertive foreign policy, particularly towards China. Both Biden and Trump have greater regulatory oversight of technology industry in their sights. The coronavirus has fast-forwarded an ongoing shift in the nature of consumption and production towards digital companies that are in turn dominated by a handful of companies that are attracting increasing regulatory scrutiny. A Biden Presidency would focus more on anti-trust regulations; whilst a Trump presidency would focus on addressing the perceived bias against conservatives. Both have professed support for improving the U.S.’s ailing infrastructure with the differences being primarily one of which states are the greatest beneficiaries and the degree of public sector involvement. Both propose robust levels of defense spending and have expressed a desire to curtail China’s perceived mercantilist and hegemonic ambitions. However, we expect Biden to pursue a less bellicose and more orderly foreign policy, which re-integrates the U.S. into global institutions and the WTO, and would more harshly respond to perceived Russian aggression and/or intervention (Chart 14). Consequently, we believe a Biden presidency would reduce the risk premia associated with heightened geopolitical risks.

Whatever the outcome of the U.S. presidential election, we expect that U.S. and global equities will rise over the coming 12 months on the back of eventual U.S. stimulus and ongoing global stimulus. A Blue Sweep would likely benefit international equities more than U.S. equities, which will face higher taxes and regulation. U.S. equities will still rise but they face more upside under a divided government in which a Republican senate either attenuates or blocks Biden’s proposed tax hikes. Moreover, larger deficits will add to an already ballooning trade deficit, which in combination with rising inflation expectations, will provide further fuel for a U.S. dollar slide.

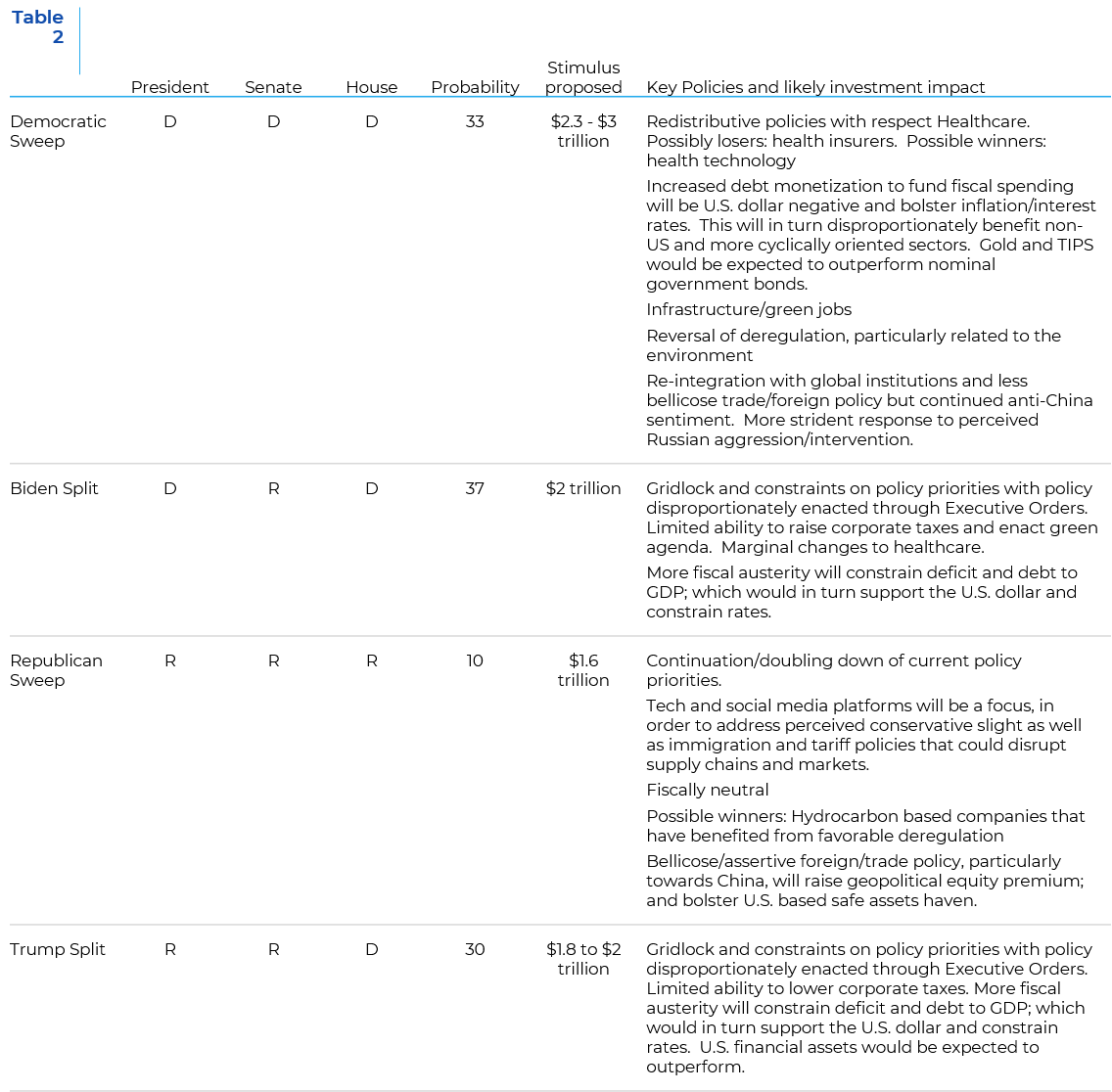

Table 2 summarizes the policy options under a Biden vs. a Trump presidency and a clean sweep vs. divided government, as well the likely investment impact.

Investment Conclusions

After an initial rout in September as negotiations over a new stimulus package first broke down, the rally in global equities in the last week of September, now appears to be in a trading range as some of the risks outlined in this research note (resurgent coronavirus cases and stalled fiscal stimulus negotiations) manifest. The counter cyclical U.S. dollar’s slide has paused, as has the sharp rise in 10-year Treasury yields.

The late September/early October rally was fueled by expectations of even greater stimulus as markets increasingly discount a Blue Wave, whereby they are willing to forgo some help today for a lot more help in Q1 2021. In this context, it makes sense that after a 10% decline in prices in early September, investors were deploying their large cash piles. A steepening yield also suggests that the bond market has been pricing in the inflationary impact (or at least, the removal of deflation risk) of a Blue Wave while keeping in mind the low likelihood of monetary tightening by the Fed. President Trump’s reelection would arguably present a risk to these assumptions as the proposed size of the stimulus under a Republican sweep is much lower. However, as previously mentioned, we believe that a more significant undiscounted risk is that, if defeated, a frustrated President Trump could easily dish out negative surprises, particularly on China relations, until he leaves office on January 20.

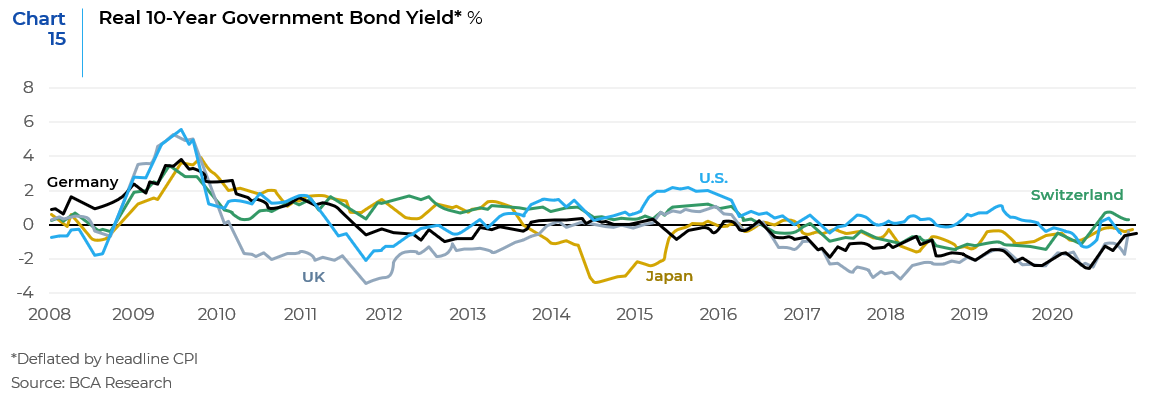

Finally, another factor behind the Late September/early October rally is the paucity of attractive alternatives, as G-10 sovereign real bond yields are mostly in negative territory (Chart 15). Legendary investor Mohammed El-Erian encapsulated the market’s current zeitgeist as follows: “Increasingly this market believes there is no alternative to equities, equities are your risk mitigator, equities are your upside claim, equities can do everything for you because everything else looks worse than equities,” El-Erian said. “That has worked. So, there is a massive fear of missing out.”

1 In his town hall on broadcast television on October 15, President Trump stated, “Peaceful transfer, I absolutely want that but ideally I don’t want a transfer because I want to win.”

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospects for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct, but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.

Watch Video

Watch Video