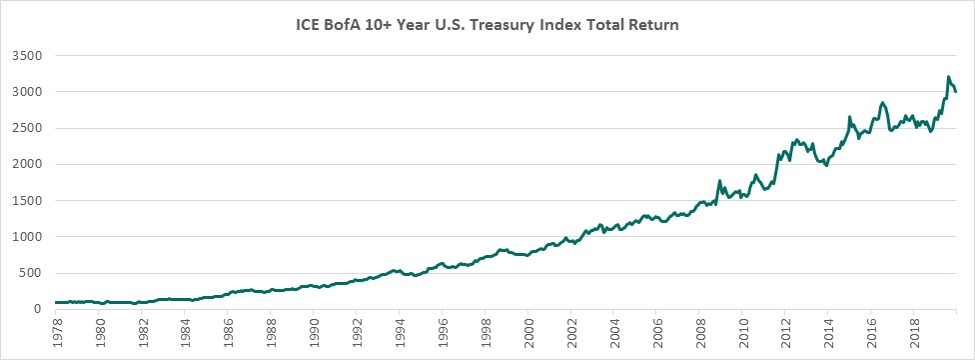

As the secular bull market in long term treasury bonds approaches its 40th year, the consensus around falling interest rates has morphed from a shared opinion to an accepted reality. Reputations and fortunes have been made and lost by adherents and skeptics respectively. While a few market participants still allow for the possibility that rates will rise meaningfully, virtually none will dare to speculate on when that might happen. We are among this skeptical but reticent group.

Source: Bloomberg

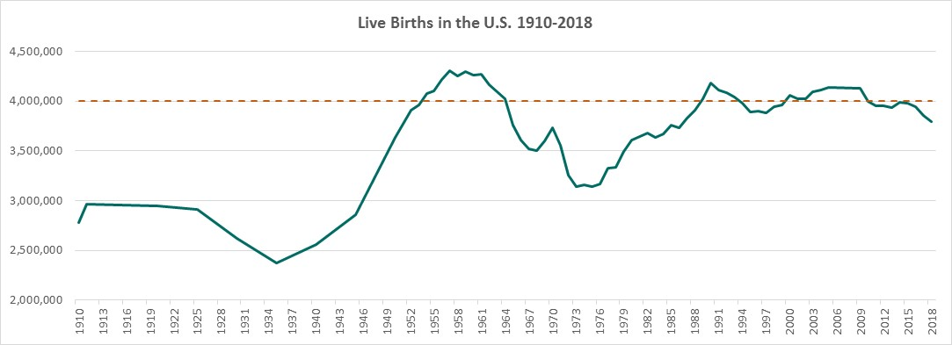

Thirty-five years of active participation in this business offers a long-term perspective that is not achievable by any other method. Years of observation have led us to see linkages between demographics, the pace of economic activity, and interest rates. Specifically, a defining characteristic of the post-World War II economic environment has been the life cycle impacts of the demographic cohort arising from increasing live births from the late 1940’s until the early 1960’s. ‘OK Boomer’, this means you.

Sources: Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, web: www.dhhs.gov.

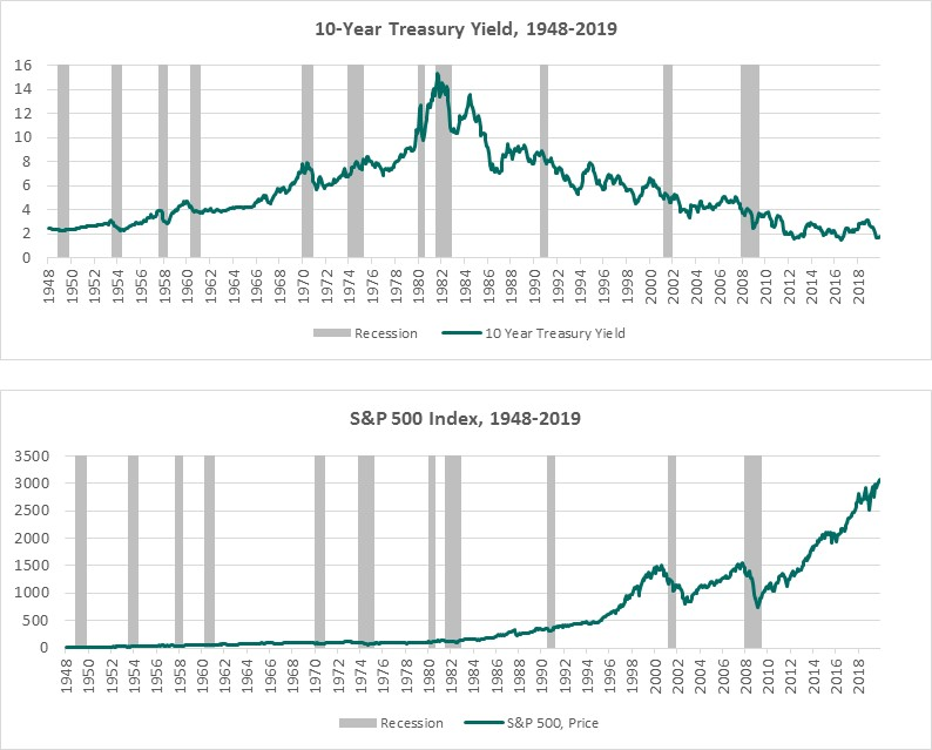

A second economic feature that has defined this post-WW II era is the secular volatility in interest rates that is virtually without precedent in the industrial era. A final feature of the era has been the steady advance of US equity markets, but this feature is hardly unique and has been observable throughout history among societies that avoided civil war, revolution, and/or external conquest. Progress has always been profitable for those who drove it and painful for those who stood in its way.

Source: Bloomberg

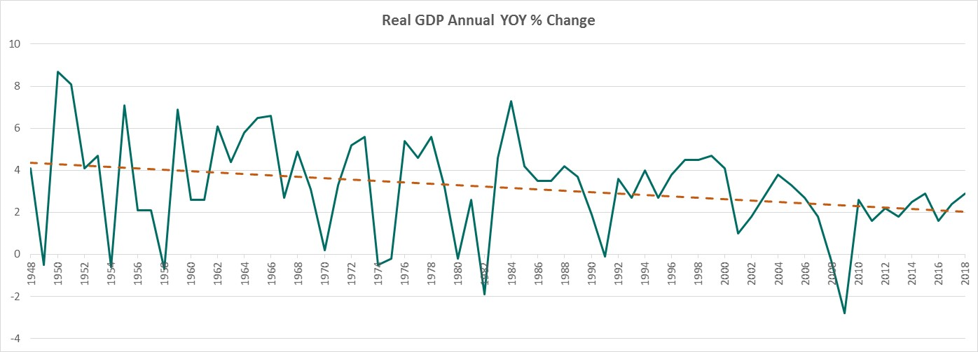

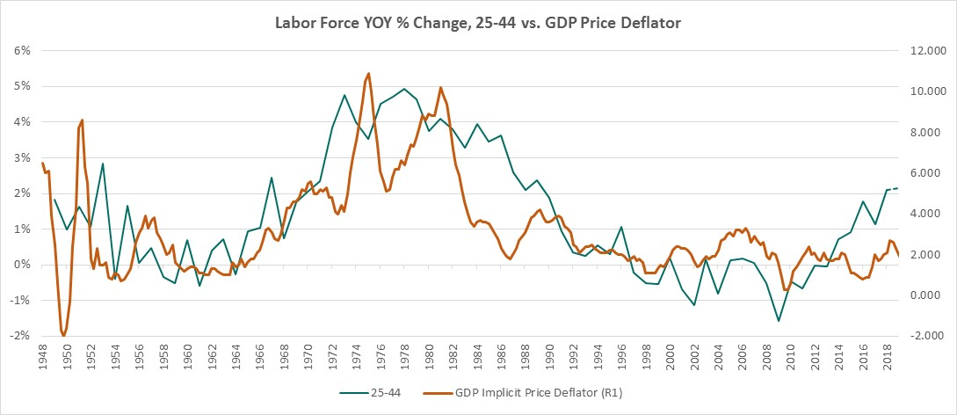

Our objective in this correspondence is to look at the impact that demographics has had on interest rates and inflation. While we are going to stop short of attempting to predict when interest rates will begin to rise on a secular basis, a close look at demographic cross currents will shed plenty of light on why this secular reversal is likely to occur. Smarter folks, than yours truly, have engaged in rigorous and prolonged academic debate as to what has caused the secular bull market in bonds. The more times this debate is revisited, the clearer it becomes that no one knows the answers. Why did we have inflation and rising rates in the 1960’s and 1970’s? Why disinflation and falling rates from the early 80’s through the late 90’s dot.com bubble? Why has monetary policy lost its effectiveness and why have the recoveries following each of the recessions in the last 30 years been progressively weaker?

Source: Bloomberg

Expansion of global trade has played an important part in reducing inflationary pressures and by association, interest rates. The advent of the information age with its limited internal demand for labor and job killing external effects has also impacted labor markets, dampening wage growth and workers’ participation in economic value creation. These two forces combined have also contributed to income inequality which skews disposition of income toward asset accumulation and away from consumption expenditures, a subject worthy of exploration. Each of these factors has played an important role in dampening inflation and interest rates and neither of them seems likely to be reversed on a sustainable basis. To find a plausible case for higher interest rates in the future, one must look to factors that are likely to reverse course. Generational demographics stand out in this regard. As we will outline in a future piece a quick survey of interest rates, inflation and GDP growth among the developing nations makes clear that demographics are a crucial variable. As an example, Japan’s longstanding economic malaise and negative interest rate scenario appears to be at least partially linked to their stalling demographics.

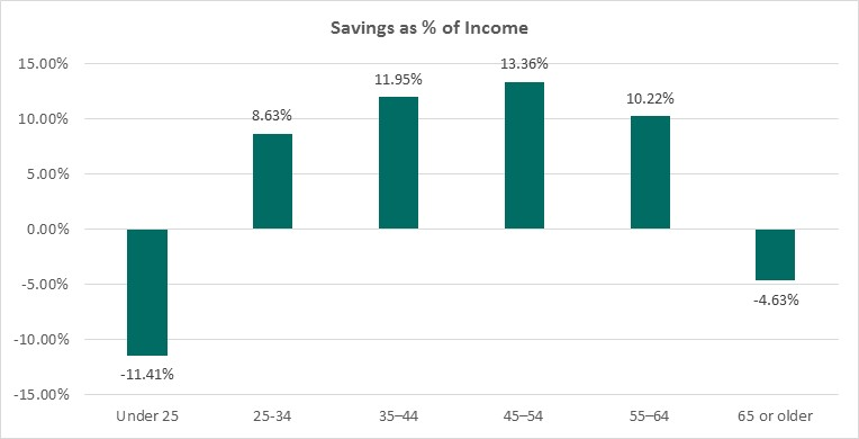

A demographic feature that is closely associated with higher interest rates and inflation is the ratio of older workers to younger workers in the labor force. When the composition of the work force shifts between a predominance of older workers to a predominance of younger workers, interest rate volatility results. This is also true in the reverse. When large numbers of younger workers begin to enter the work force, inflationary pressures build based on young workers’ appetite for big-ticket items associated with household formation and on their tendency to income average their expenditures based on expected career earnings. Interest rates then rise with inflation to maintain expected real return levels for bond investors. The inflationary impact in this scenario is magnified because most growth in wages occurs during the first half of a career as productivity builds. Cyclical growth therefore has its greatest income effect on younger workers whose productivity is still rising and who are spending the associated wage growth at a higher rate than their more mature colleagues who have begun to accumulate assets for retirement. In a work force dominated by older workers, compensation effects of economic growth are muted, and corporate profits tend to benefit from faster economic growth. This growth in profit margins, coupled with the tendency of older workers to save and invest, leads to stronger performance in financial markets and asset price inflation rather than tangible goods price inflation.

Note: The savings rates for each age group are calculated as the average of Year 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2018.

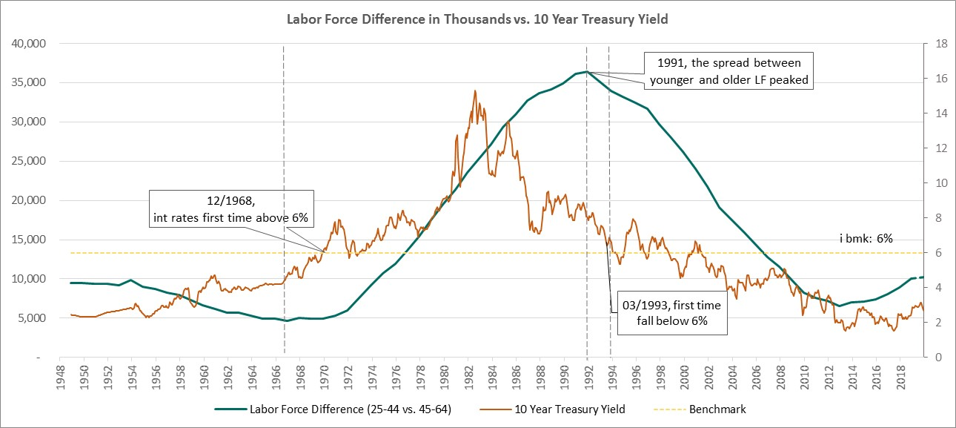

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

10-year treasury yields crossed 6% for the first time ever in 1969 which was the same year that the number of workers in the 25-45-year-old age bracket began to increase relative to the 45-65-year-old bracket. Treasury yields did not fall meaningfully below the 6% level until March 1993 which was just 15 months after the spread between younger workers and older workers peaked in December 1991. The inflation of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s began at about the same time that the growth in the younger component of the work force began to accelerate as the post WW II generation began to enter the work force in large numbers. Inflation and 10-year treasury yields peaked in 1981 shortly after the growth of the 25-45-year old component of the work force peaked.

Source: Bloomberg, Bureau of Labor Statistics

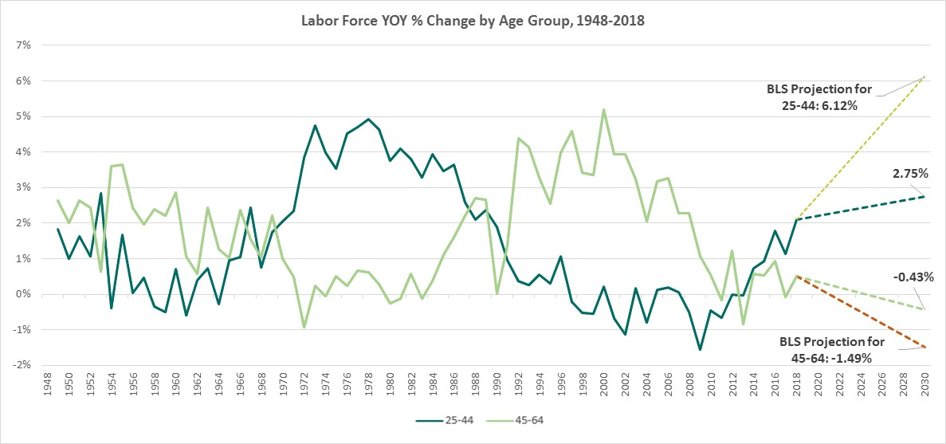

We expect the growth rate of the younger component of the work force to exceed the growth of the older component of the work force over the next ten years. Our simple organic population estimate (using constant age cohort work force participation rates and calendar driven changes in age cohort composition) is muted relative to the Bureau of Labor Statistics forecast which bakes in more assumptions about workforce participation and includes immigration. In either event, a rejuvenation of the workforce seems to be almost certain to occur over the next ten years and beyond.

Note: Our labor force projections are based on expectations of the future size and composition of the population. We estimate in 2030, the labor force participation rates for each age group remains constant at the 2018 level.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, BLS methodology for labor force projections:

https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2019/article/projections-overview-and-highlights-2018-28.htm

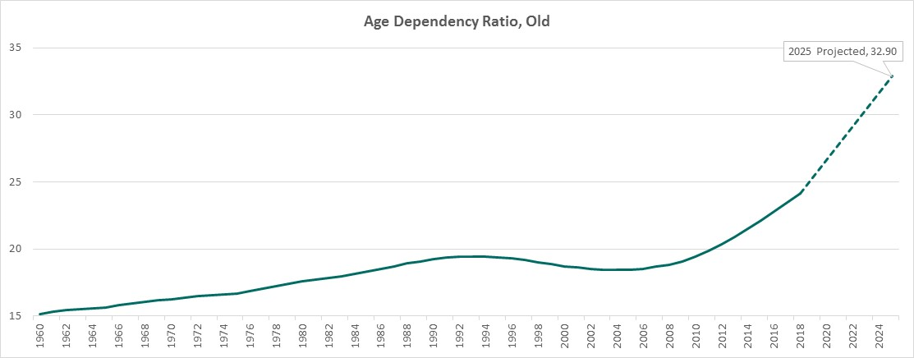

We expect the “savings glut” that developed post 1990 to shrink meaningfully as the younger component of the work force demonstrates its typically higher marginal propensity to consume. This trend will be magnified by the flood tide of Boomer retirements which will ignite systematic dissaving as income from assets set aside for retirement is fully expended along with ever-increasing components of principal. This consumption of principal is a result of underfunded retirement accounts that failed to grow due to low interest rates during the savings glut and due to the substantial elimination of defined benefit pensions in many segments of the economy. The demographic shock of the growth of the younger component of the work force may or may not be as numerically significant now as it was in the 1970’s. Combined with the added impact of higher dependency ratio’s resulting from an aging population it will add extra pressure on interest rates, inflation, and the valuation of investment assets.

Source: World Bank, Projected Data from OECD

The implications are for better long-term performance of short duration stocks relative to long duration stocks and strong outperformance of short and intermediate term fixed income. Be wary of lofty valuations and high-end real estate because consumption patterns will shift. Be especially wary of long bonds because as rates rise in response to inflation, yield curves will almost certainly steepen. A final caveat to these ideas is that if this opinion does not prove out over the years, you will have to take it up with a Millennial or a Zoomer because this Baby Boomer will almost certainly have been put out to pasture by then.

Cheers and Happy New Year!