Historical Overview of Global Reserve Currencies

For centuries, great economic powers have seen their currencies used beyond their borders. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the British pound sterling was the world’s leading reserve currency. At its height, Britain was the world’s largest exporter and over 60% of global trade was invoiced in pounds. After World War I and especially World War II, economic leadership shifted to the United States. The U.S. emerged from WWII with a significant share of global GDP, a stable democracy, and vast gold reserves, positioning the U.S. dollar to replace the pound as the primary reserve currency.

In 1944, 44 nations signed the Bretton Woods Agreement, formally making the U.S. dollar the anchor of the post-war international monetary system. Under Bretton Woods, the dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce, and other currencies were in turn pegged to the dollar. This system cemented the dollar’s dominance and foreign central banks held dollars which were convertible into U.S. gold as the core reserve asset. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, this arrangement ensured the dollar’s centrality in global finance.

By the late 1960s, however, strains had emerged. The U.S. had created large numbers of dollars globally through aid, military spending, and imports such that dollar liabilities abroad exceeded U.S. gold reserves. In 1971, facing a run on U.S. gold, President Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold, effectively breaking the Bretton Woods system and letting the dollar float. Despite this shift, the dollar retained its dominance—bolstered by confidence in U.S. institutions and the emergence of the petrodollar system, which ensured that oil exports from OPEC nations would be priced in dollars.

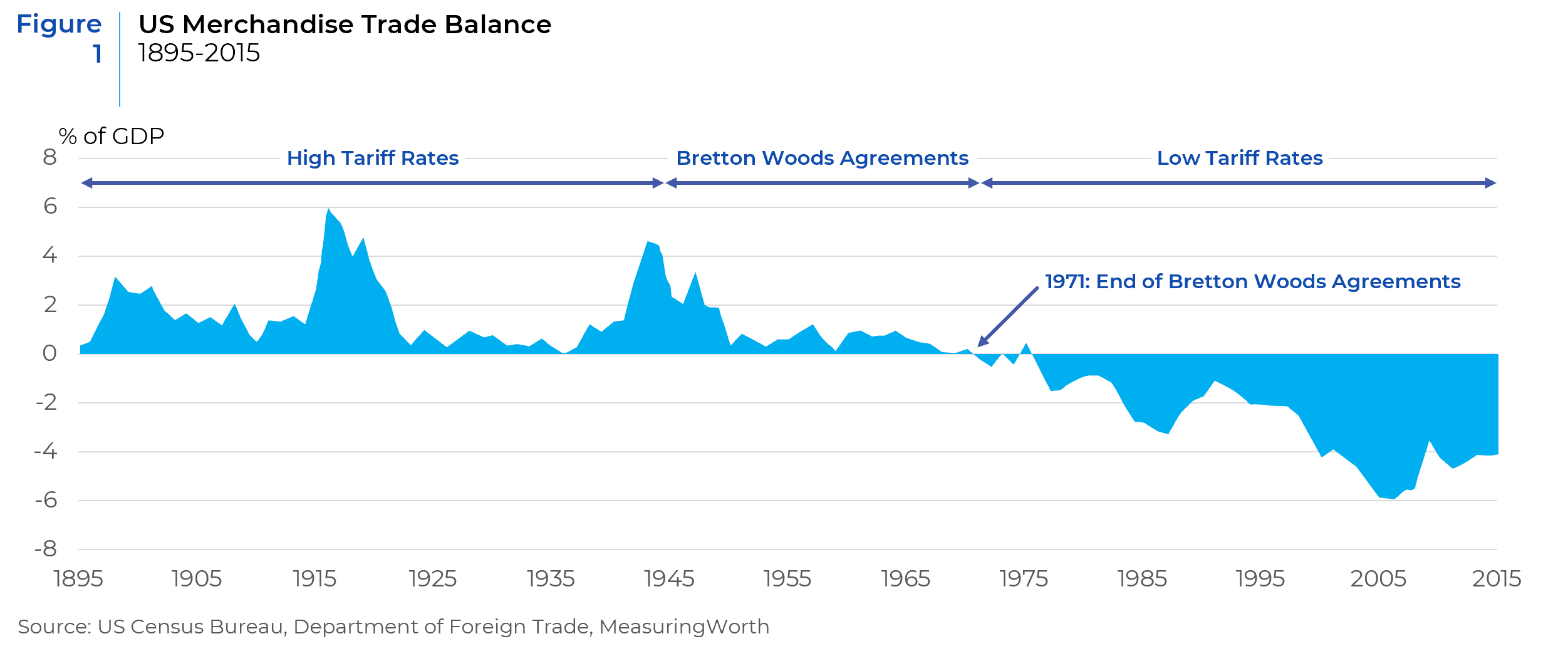

Without the gold constraint, U.S. monetary and fiscal policy became more flexible – and the U.S. began running trade deficits more consistently. In 1985, the United States officially shifted from a net creditor to a net debtor nation, effectively accepting the burden of supplying the world with dollars via ongoing trade deficits. Since the 1980s, the U.S. has continuously run an annual trade deficit. Figure 1 illustrates this historic turning point: the U.S. ran trade surpluses or balanced trade through much of the early 20th century, but after the early 1970s the balance plunged into persistent deficit. In recent decades, these deficits have grown enormously in dollar terms.

Why Reserve Currency Status Leads to Trade Deficits

Several economic concepts help explain the link between having the world’s reserve currency and running chronic trade deficits. Key among them are the Triffin Dilemma, balance-of-payments accounting identities, and the global demand for safe assets.

The Triffin Dilemma: In 1960, economist Robert Triffin pointed out a fundamental paradox facing the issuer of a reserve currency. To satisfy other countries’ demand for foreign exchange reserves, the issuer must supply large quantities of its currency to the world. In practice, this means the reserve currency country must run net international outflows of its currency, typically through a trade deficit. In other words, other nations can only accumulate dollars if the United States is sending out more dollars by importing more than it exports or investing abroad. Triffin argued this creates a conflict as the U.S. must run deficits to provide liquidity to the world, but persistent deficits can undermine confidence in the currency long-term. This trade-off between short-term global liquidity needs and long-term stability is the essence of the Triffin Dilemma. During the Bretton Woods era, Triffin’s warning was that the U.S. could not indefinitely back the growing supply of dollars with gold. Today, the dilemma manifests as a conflict between the U.S.’s domestic goal of balanced trade and the international need for more dollars in circulation.

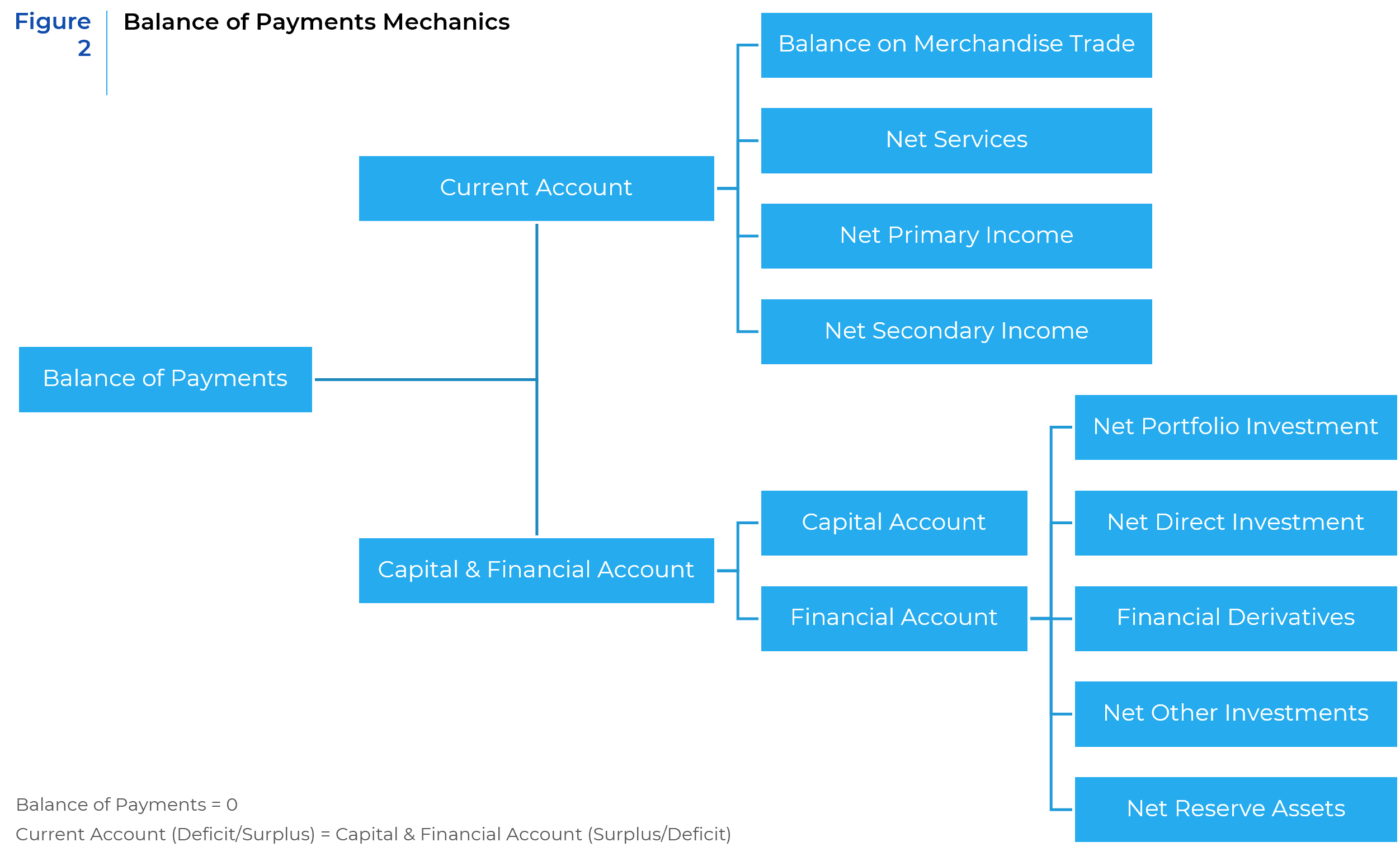

Balance of Payments Mechanics: Balance of Payments = Balance of Current Account + Balance of Capital & Financial Account. The Balance of Payments, which should sum to zero, represents the total of all transactions between a country’s residents and the rest of the world during a specific period. Current Account reflects transactions involving the exchange of goods and services, income from investments, and unilateral transfers like foreign aid and remittances. Capital Account tracks the transfer of ownership of assets, such as patents and intellectual property, and the flow of capital. Financial Account records the changes in a country’s ownership of international financial assets, including investments, loans, and currency exchanges. If a country runs a current account deficit which includes the trade balance, it must have an equal and opposite capital and financial account surplus (see Figure 2). This is an identity: “the current account is always offset by the capital and financial account so that the balance of payments sums to zero.”

For the U.S., the persistent trade deficits are matched by foreign investment into U.S. assets or foreign lending to the U.S. In practice, when Americans buy more goods from overseas than foreigners buy from the U.S., dollars flow out. Those dollars return as foreign purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds, stocks, real estate, etc. The result is that the U.S. finances its import spending by selling financial assets to the rest of the world. This cycle is self-reinforcing: the trade deficit provides dollars to foreign nations, and those dollars are used to acquire U.S. assets, which in turn keeps the dollar in high demand. It also means the U.S. can consume more than it produces by borrowing from abroad, a privilege enabled by the dollar’s reserve status.

Global Demand for Dollar Assets: The U.S. dollar’s dominance is underpinned by trust in U.S. financial markets and government debt as “safe assets.” Foreign central banks and investors have an appetite for reliable, stable stores of value, and U.S. Treasury securities are viewed as one of the safest assets in the world. This creates a global savings glut directed at dollar assets. As a result, the U.S. government can readily finance budget deficits by issuing Treasury bonds that are bought by overseas authorities and investors. This strong foreign demand for dollar assets contributes to the U.S. running current-account deficits year after year. In effect, the world profits from U.S. deficits. Other countries get a safe place to park their surpluses, and the U.S. economy gets an influx of cheap capital. However, this high demand for dollar assets has an unintended consequence- it supports a stronger dollar, which makes U.S. exports relatively expensive and imports cheaper—further widening the trade deficit. As the Council on Foreign Relations notes, strong global demand for dollars can come “at a cost to export-heavy U.S. states, resulting in trade deficits and lost jobs.”

Notably, what was once termed America’s “exorbitant privilege” – the benefit of borrowing easily in its own currency – has a flipside often called an “exorbitant duty.” Because global investors and central banks crave dollar assets, the U.S. ends up supplying them by issuing large amounts of debt and currency. In other words, the dollar is dominant because there is so much U.S. debt for the world to buy. This paradoxical situation means the U.S. must continually run deficits to satisfy the rest of the world’s appetite for dollars, even if that means growing external indebtedness

U.S. Trade Deficits and Global Reserve Holdings

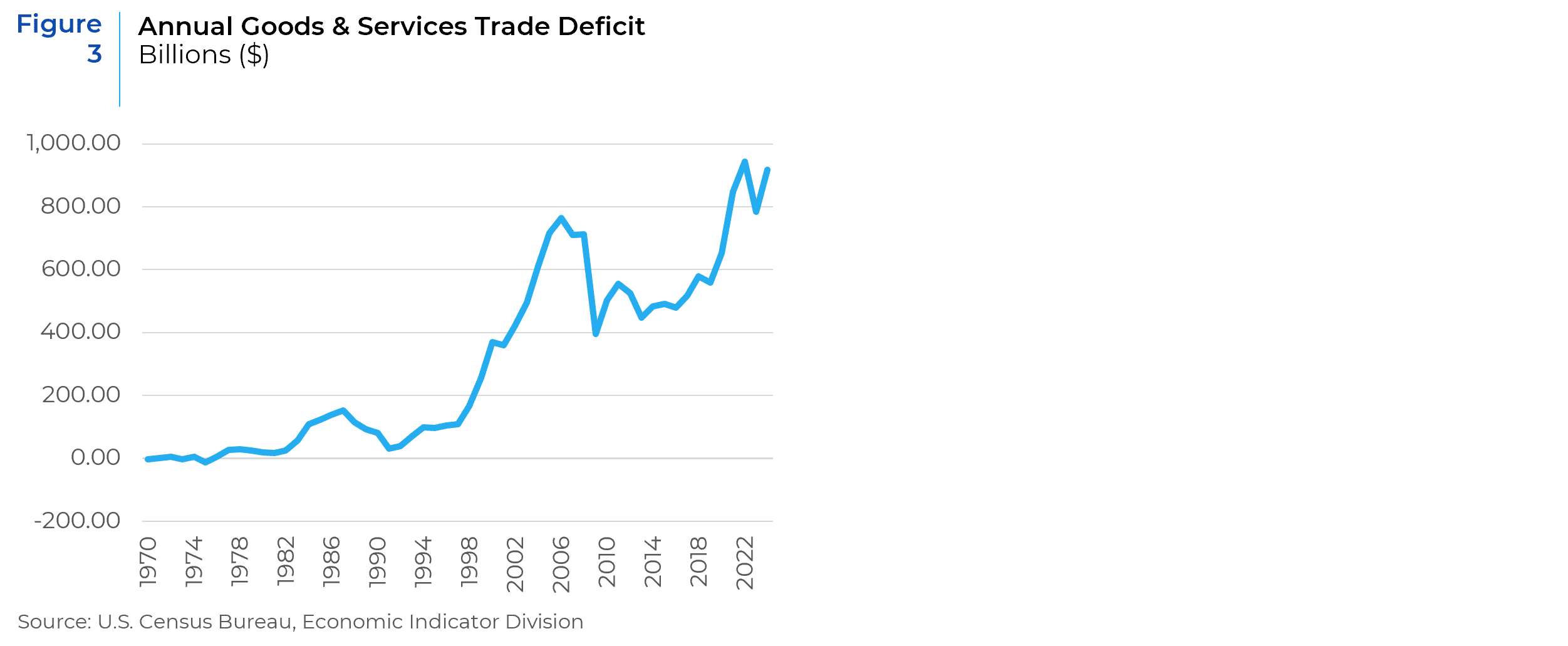

U.S. Trade Balance Trends: The theoretical expectations above are borne out in real-world data. The United States has consistently run a trade deficit for the past several decades. This deficit began in the late 1970s and widened significantly from the 1980s onward. It has persisted through recessions and booms, through periods of dollar strength and weakness – a structural imbalance rather than a cyclical one. In the 1990s the deficit was relatively modest, but it exploded in the 2000s. Figure 3 shows the U.S. trade deficit in recent years, climbing toward $1 trillion by 2022, decreasing some in 2023, and then breaching the $900 billion mark again in 2024. Even with short-term fluctuations, the trend since 1990 has been a growing deficit, in line with the U.S. dollar’s continued role as the reserve currency. It is no coincidence that as international dollar reserves accumulated, the U.S. became a net debtor to the world.

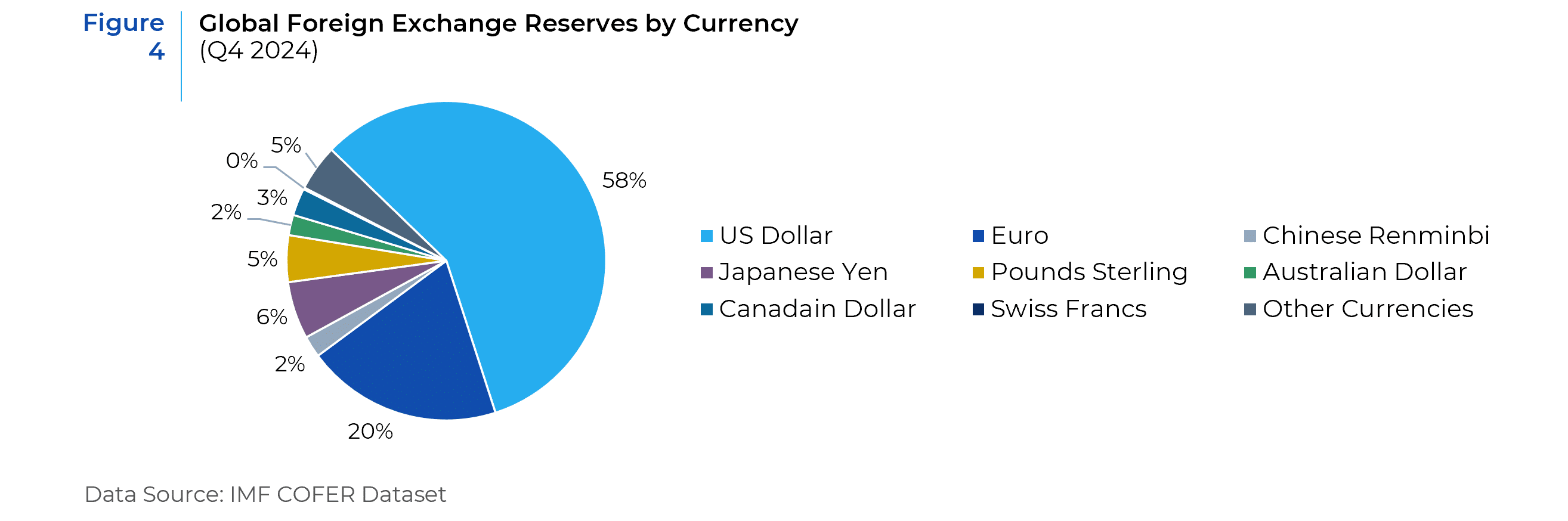

Global Reserve Currency Holdings: The U.S. dollar remains the centerpiece of international reserves. As of the end of 2024, about 58% of global foreign exchange reserves are held in U.S. dollars, far more than any other currency. For comparison, the euro (the second-ranking reserve currency) makes up about 20%, and smaller shares are held in the Japanese yen (~6%), British pound (~5%), and others (including China’s renminbi, which is still only ~3% of global reserves). Figure 4 provides a breakdown of the currency composition of worldwide reserves. Countries accumulate dollar reserves as a safety net for international transactions and financial stability – for example, to defend their currency in a crisis or to secure the ability to pay for imports like oil, which are priced in dollars.

The large share of dollar reserves means that changes in other countries’ reserve accumulation directly impact U.S. external balances. When countries like China run big trade surpluses with the U.S., they reinvest much of those dollar earnings into U.S. Treasury bonds and other dollar assets, swelling their reserves. This recycled flow keeps U.S. interest rates lower than they might otherwise be and finances U.S. consumer and government spending. The downside, as we have seen, is that the mechanism to supply these reserves is the U.S. running deficits. In effect, the U.S. trade deficit is supplying the world with the dollars it demands.

Sustainability and Risks for the Issuing Country

Is this arrangement – perpetual U.S. trade deficits in exchange for the dollar’s reserve status – sustainable, and what risks does it pose? There are two sides to consider: benefits to the U.S. and potential dangers.

On one hand, the U.S. enjoys significant advantages from issuing the world’s reserve currency. It can borrow internationally in its own currency at low interest rates, and the high global demand for Treasuries keeps U.S. financing costs down. The U.S. can run deficits without immediate solvency concerns, as there is usually eager foreign demand to buy its debt. This “safe haven” status also gives the U.S. leverage in international affairs – for instance, the ability to impose financial sanctions. The dollar’s role therefore allows the United States to “borrow money more easily” and even use its currency as an instrument of power.

However, there are notable risks and long-run costs. First, continuous deficits mean the U.S. is accumulating debt to foreigners. While U.S. debt is considered safe, Triffin’s paradox suggests a point may eventually be reached where foreign confidence wavers – either because the debt has grown too large or because domestic U.S. policies undermine the dollar’s value. The issuer of a reserve currency faces the challenge of maintaining trust; if investors fear the U.S. will “debase” the dollar to manage its debt, they could reduce their dollar holdings, triggering a dollar decline or financial turmoil.

Secondly, the reliance on foreign capital inflows could become a vulnerability. If major reserve holders like China or Japan ever lost appetite for U.S. assets, the U.S. would face pressure to adjust. A sudden pullback from dollar assets or even a slower diversification away or “de-dollarization” could lead to a weaker dollar and higher U.S. interest rates, constraining the American economy. While outright dumping of reserves is unlikely, there is a risk that the political weaponization of the dollar – such as extensive sanctions – encourages rival powers to seek alternatives to reduce their dependence on USD. Recent events, like sanctions on Russia and heightened U.S.-China strategic competition, have indeed prompted some countries to explore trading in other currencies. Over time, such shifts could chip away at the dollar’s dominance.

Another concern is the domestic structural impact. Running persistent trade deficits can hollow out certain industries, as U.S. consumption is met increasingly by imports. This can lead to job losses in manufacturing and contribute to regional economic disparities. The reserve currency status, by keeping the dollar strong, makes U.S. exports less competitive internationally, which some argue has impacted manufacturing employment in the U.S. The U.S. economy has benefitted from cheaper imports, but the social and political repercussions of deindustrialization are part of the cost that must be managed.

Is the situation sustainable? In the near and medium term, most experts believe the dollar-centric system will continue. Competing currencies face significant hurdles. The euro, while major, is hampered by a lack of unified fiscal backing and periodic crises. The Chinese renminbi is not fully convertible, and China’s financial system lacks transparency, limiting its appeal as a reserve asset. Other currencies like the Japanese yen or British pound are tied to smaller economies. Even gold or newer digital currencies cannot easily replicate the full spectrum of stability, liquidity, and wide acceptance that the dollar enjoys.

That said, long-term risks should not be ignored. The sustainability of perpetual deficits depends on the world’s continued willingness to hold U.S. assets. If U.S. fiscal policy led to unsustainable levels of debt or high inflation, confidence in the dollar could erode. The U.S. would then face pressure to correct its external imbalance through a weaker dollar or reduced consumption – an adjustment that could be painful if forced suddenly. Additionally, as global economic power becomes more multipolar, it is conceivable that a multi-currency reserve system could emerge in the future (for example, greater use of the euro or China’s renminbi alongside the dollar). Such a shift would reduce the world’s need for additional dollar liquidity, meaning the U.S. would no longer be able to run large deficits without consequences.

Conclusion

In summary, the United States’ position as issuer of the world’s predominant reserve currency is a double-edged sword that helps explain its persistent trade deficits. The world’s demand for dollars and dollar-denominated safe assets has required the U.S. to supply an ever-growing stock of currency, accomplished by importing more than it exports year after year. Balance-of-payments dynamics ensure that those extra dollars circulating abroad come back as investments in the United States, funding America’s deficit spending. The result has been decades of trade deficits that are not merely a policy choice, but in many ways a structural outcome of the dollar’s global role.

While this arrangement affords the U.S. significant benefits — from cheap capital to enhanced geopolitical influence — it is not without costs or risks. The U.S. must manage a growing external debt, and contend with impacts on domestic industries. In the near future, no single challenger seems poised to displace the dollar, making the current system likely to endure. However, the U.S. cannot take its reserve currency status for granted. Prudent fiscal and monetary management is required to sustain confidence in the dollar. A loss of faith by foreign holders or a fragmentation of the international monetary order could expose the U.S. to abrupt adjustments. Thus, being the world’s reserve currency is a privilege that demands careful stewardship. It places the onus on U.S. policymakers to ensure that this unique position remains an overall benefit and not a liability to the nation in the long run.

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospective clients for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.